Yesterday’s post described the history of personal computing platforms over the past 37 years. It showed a distinct shifting of “eras” between traditional personal computing and the emergent mobile computing represented by device-based platforms.

Underlying these lives (and deaths) of platforms were the growth (and decline) of fortunes of companies and people. I hoped that by observing these patterns insight could be gained into the conditions for success or failure.

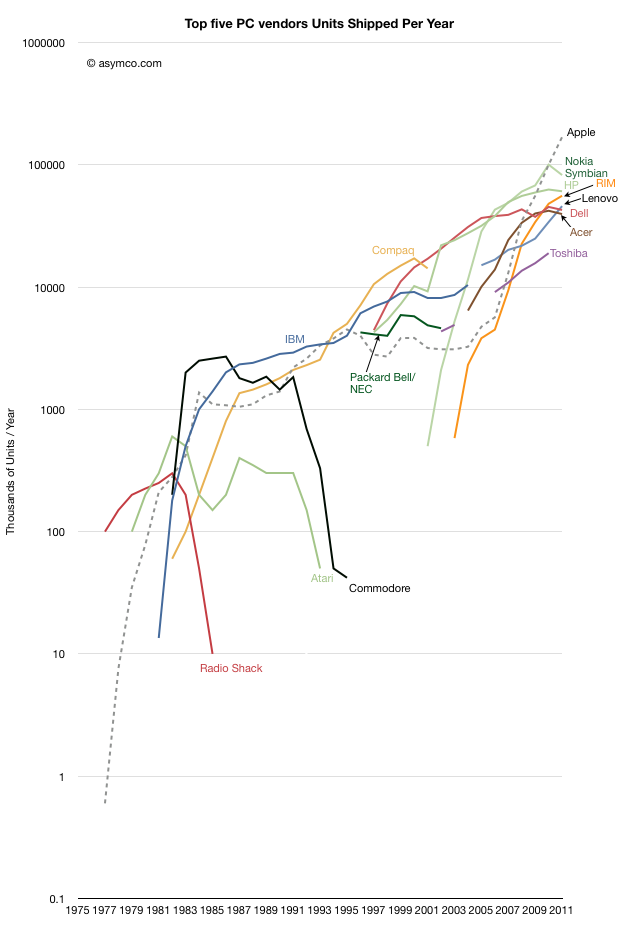

The following graph shows the companies which were predominant (in the top five ranking by shipments[1]) during each year of the industry’s history and the volumes they were able to obtain during that period. I also added Nokia and RIM as examples of the challengers coming from mobile devices.

It’s a difficult graph to interpret. The pattern I observed was that most companies were not able to sustain presence in the top five ranking for long. Indeed, regardless of having one’s own platform or being a licensee, companies seemed to fade reliably. Some were acquired, some sold their operations but there is a distinct impermanence to their prosperity.

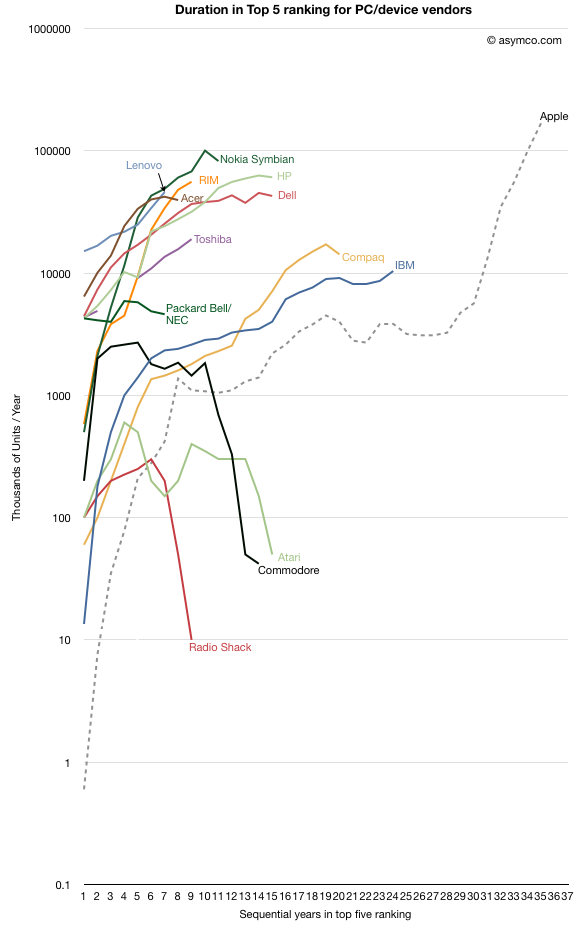

To sharpen this perspective of longevity I indexed each company to the point when they entered the “prosperity zone” and measured their staying power within it. The following graph shows these indexed lives.

Apart from Apple, IBM remained in the business the longest (24 years). Compaq was second with 20 years before being bought by HP. HP and Dell are still operating after 15 years, having tied Atari and Commodore. After these ancients, the upstarts Nokia and RIM are struggling to remain relevant after 10 to 12 years.

Then there are the transients like Packard-Bell/NEC, Toshiba, Radio Shack and Fujitsu which lasted less than 10 years. The newest PC companies are all from China or Taiwan: Acer, Asus and Lenovo. Their longevity cannot be called yet though Acer seems to be in decline. Lenovo, which took over IBM’s brands continues to grow. However, as yesterday’s post showed, without diversification into devices, pure PC makers are likely to fade.

But besides this interesting history lesson, there is a deeper, unsettling observation. The scale of these periods of prosperity is far shorter than the average person’s career. Indeed, the entire time span of the study is 35 years, about the time an average person will be employed. All the companies failed to maintain prosperity over this time frame.

These are a small sample, flawed by showing only hardware units, but I consider it a proxy for the overall technology market. Software-only or services companies have had no better records.

The implications for company managers and workers is profound. Chances are that the business you work for will not prosper for more than a decade and will reward you for an even shorter period. Similarly, as witnessed by the P/E ratios, investors have given up on this industry as one with any quality of earnings.

There is no “rule” that this has to be so. The high mortality rate and short longevity of technology companies is a consequence of a failure to manage innovation and disruption. Apple may be an exception–one I think worth studying. Though not always prosperous, it has managed to survive, being the only company from the early era of personal computing to still be operating in the industry. Indeed, it’s now the most prosperous. Maybe it’s a fluke, but I rather think it’s due to an ability to re-define itself as the market shifts. Its essential quality being an ability to disrupt itself.

And if we think about it this way, ultimately, longevity is more important than prosperity. Without patience there is nothing but chance determining prosperity. The fate of more than company finances rests in the balance.

Notes:

- Apple did not maintain a position in the top 5 throughout this period but is shown as a benchmark as it remained in the same business throughout this period.

Discover more from Asymco

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.