A glance at Nokia and RIM’s market values today shows that they are both valued below book. With respect to RIM,

The company’s share price has collapsed in the past year, and it is now only valued at about $5.4 billion, down from $84 billion at its peak in 2008. Excluding its cash and the estimated value of its patents, RIM’s device business and its 78 million subscribers around the world are in aggregate worth less than $1 billion to investors.

Analysis: RIM’s new woes seen speeding loss of BlackBerry users – Yahoo! Finance

With respect to Nokia,

MKM: We are downgrading Nokia to Sell from Neutral following our U.S. retail Lumia model checks. We assume no value for the handset business and no value for the roughly four billion euros [about $5 billion] in net cash.

Nokia Suffers From Hang-Ups – Barrons.com

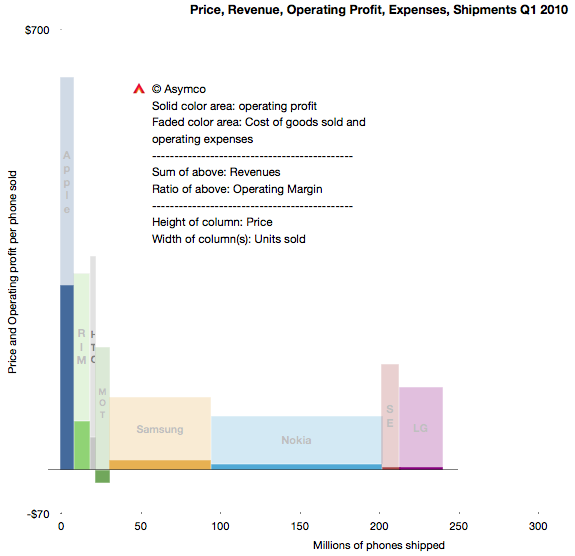

Three years ago the situation was dramatically different. RIM’s share price was six times higher and Nokia’s about four times higher. Here’s what the market looked like in Q1 2010:

This summary view shows individual competitors in the phone market as well as their combined total volumes. The profitability/volumes/pricing can be visualized as well as margins and revenues.

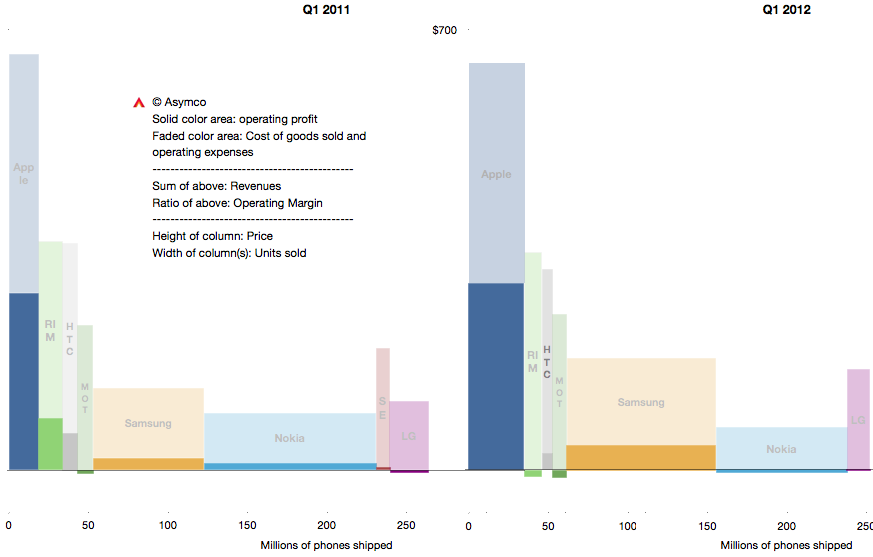

The same visual summary is presented for the first quarters of 2011 and 2012 below:

The change may be subtle to the untrained eye, but it can be summarized as contraction for most vendors and expansion for Apple and Samsung. RIM and Nokia not only contracted in terms of revenues and volumes but also, crucially, lose money.

I’ve written about this before (many times.) But it’s important to repeat again that this is a very short time span. Only three years separate the top chart from the bottom right. The “shape” of the market participants has not changed much but a tipping point has been crossed. This is the point where some participants are disrupted enough that they cannot recover.

Did it happen in 2010, 2011 or 2012? We’re only looking at data which results from hundreds of decisions and thousands of actions. It’s improbable that there was a single moment when the shift occurred or a single decision that caused it. But it’s equally improbable that the disrupted could have countered any of the actions that got them to this point.

The cause (and remedy) for disruption is never found in a single act. It’s a process and a way of operating and thinking. Is management to blame? That’s always the answer. But how did management go from being smart to foolish so quickly and why did all managers in a firm, even an industry, conspire to become foolish at the same time?

If you study the decisions on a day-to-day basis, management consistently applies all the lessons they learned that led to success in the past. But these lessons lead to decisions that end up with exactly the worst result possible.

The crux of this dilemma is that doing the “right thing” leads to the wrong result. In a comment I questioned the possibility of management in a public company solving the dilemma.

Some have argued that public companies with professional managers entrusted with fiduciary responsibility are inherently incapable of solving the innovator’s dilemma and are thus doomed to be disrupted. I’m starting to believe the argument. Whenever you as a manager try to work out the solution to the dilemma, you encounter a value destroying obstacle that cannot be surmounted while maintaining your position in the company. [As you attempt to solve it, you lose your position] Your successor won’t make the same mistake and [thus] the whole enterprise collapses.

There are counter-examples however. The reason Apple should be studied is that it gives hope that they have cracked this problem.

Discover more from Asymco

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.