“Within five years after discount retailing pioneer Korvette’s opened its first store in 1957, over a dozen copycat discounters had emerged. In contrast, the giant discount furniture retailer IKEA has never been copied. The company has been slowly rolling its stores out across the world for [close to 50] years; and yet nobody has copied IKEA.

Why would this be? It’s not trade secrets or patents. Any competitor can walk through its stores, reverse engineer its products and copy its catalog. It can’t be that there is no money to be made: its owner Ingvar Kamprad is the third richest person in the world. And yet nobody has copied IKEA.

Our sense is that the other furniture retailers have followed the positioning paradigm and defined their business in terms of product and customer categories, which are readily copied. Levitz Furniture, for example, sells low-cost furniture to low income people. Ethan Allen sells colonial furniture to wealthy people.

IKEA, in contrast, has organized its business around a job to be done: “I need to furnish my apartment (or this room) today.” When this realization occurs to people anywhere in the developed world, the word IKEA pops into their minds. IKEA is organized and integrated in a completely different way than any other furniture retailer in order to do this job as well as possible.”

Integrating Around the Job to Be Done (Clayton Christensen, Harvard Business School; Scott Anthony, Innosight LLC, Scott Cook, Intuit; Taddy Hall, Advertising Research Council).

IKEA is the world’s leading furnishing retailer and an amazing success story. As Christensen points out the success is all the more perplexing because it seems perfectly defensible. Nobody has tried to duplicate or undermine IKEA.

Positioned around a clear job-to-be-done it integrated design, manufacturing and distribution (including warehousing) as well as “big box” retailing as an experience.

This may sound familiar.

Apple’s entry into retail depended on a clear job-to-be-done, design, carefully selected merchandise and retailing as an experience. Similar to IKEA, Apple also became a dominant player in its segment and even achieved seventeen times better performance than the average US retailer in terms of sales per square foot.

At first glance they seem to be similar businesses in terms of strategy or “architecture” but how do the actual businesses stack up? Can we find data to support any claim of similarity.

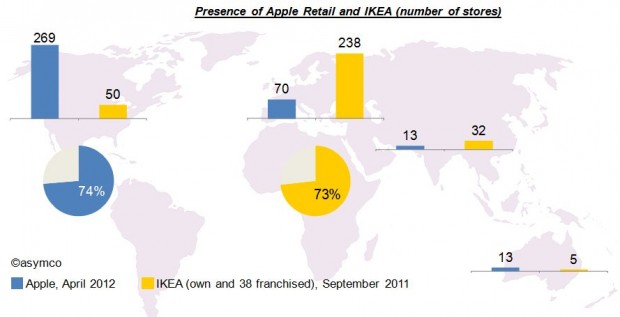

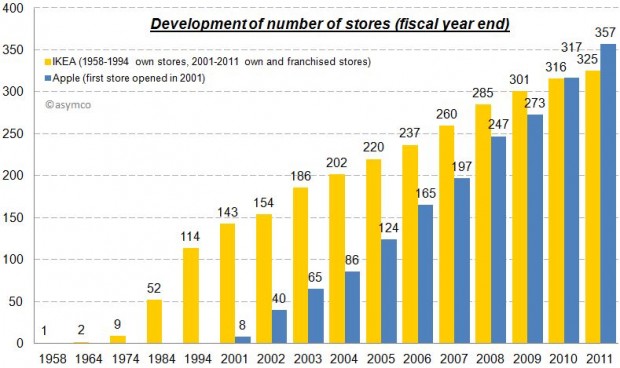

Let’s first have a look at the geographic focus of both companies. The graphic below shows that Apple’s retail operations are focused on North America with 74% of its 365 stores in the USA and Canada. By contrast, and maybe as much based on its origin, 73% of IKEA’s 325 stores are located in Europe[2].  Unlike Apple however, IKEA has grown much more slowly. IKEA’s first store was opened in 1958 and had 6,700 sqm (72,110 sqf). The first two Apple stores opened in May 2001. Since then the number of Apple stores grew significantly faster (CAGR: 46%) and surpassed the number of IKEA stores in 2010.

Unlike Apple however, IKEA has grown much more slowly. IKEA’s first store was opened in 1958 and had 6,700 sqm (72,110 sqf). The first two Apple stores opened in May 2001. Since then the number of Apple stores grew significantly faster (CAGR: 46%) and surpassed the number of IKEA stores in 2010.

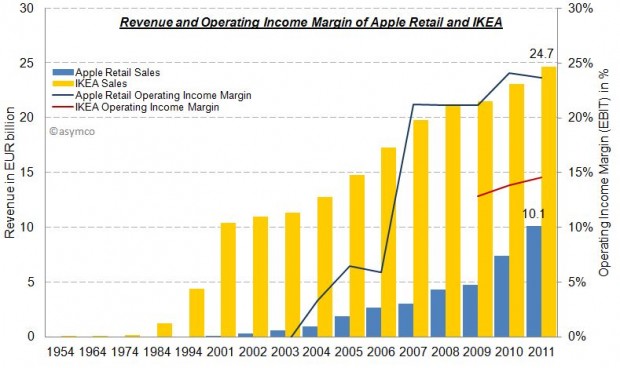

The other difference is in sales growth. In 1954 IKEA’s revenue amounted to approximately $1 million but has grown steadily (note in chart below that first five bars represent decades). In contrast, Apple has grown more rapidly and is also more profitable in terms of margin.

Part of the difference in growth is that Apple was able to subsidize its entry: Apple’s retail operations were loss making for the first three years while IKEA had to rely on financing from its own cash flows.

Eventually, Apple retail became self sufficient and is now more profitable than IKEA. The following charts provides an overview of the economics of Apple’s retail operations and IKEA side-by-side:

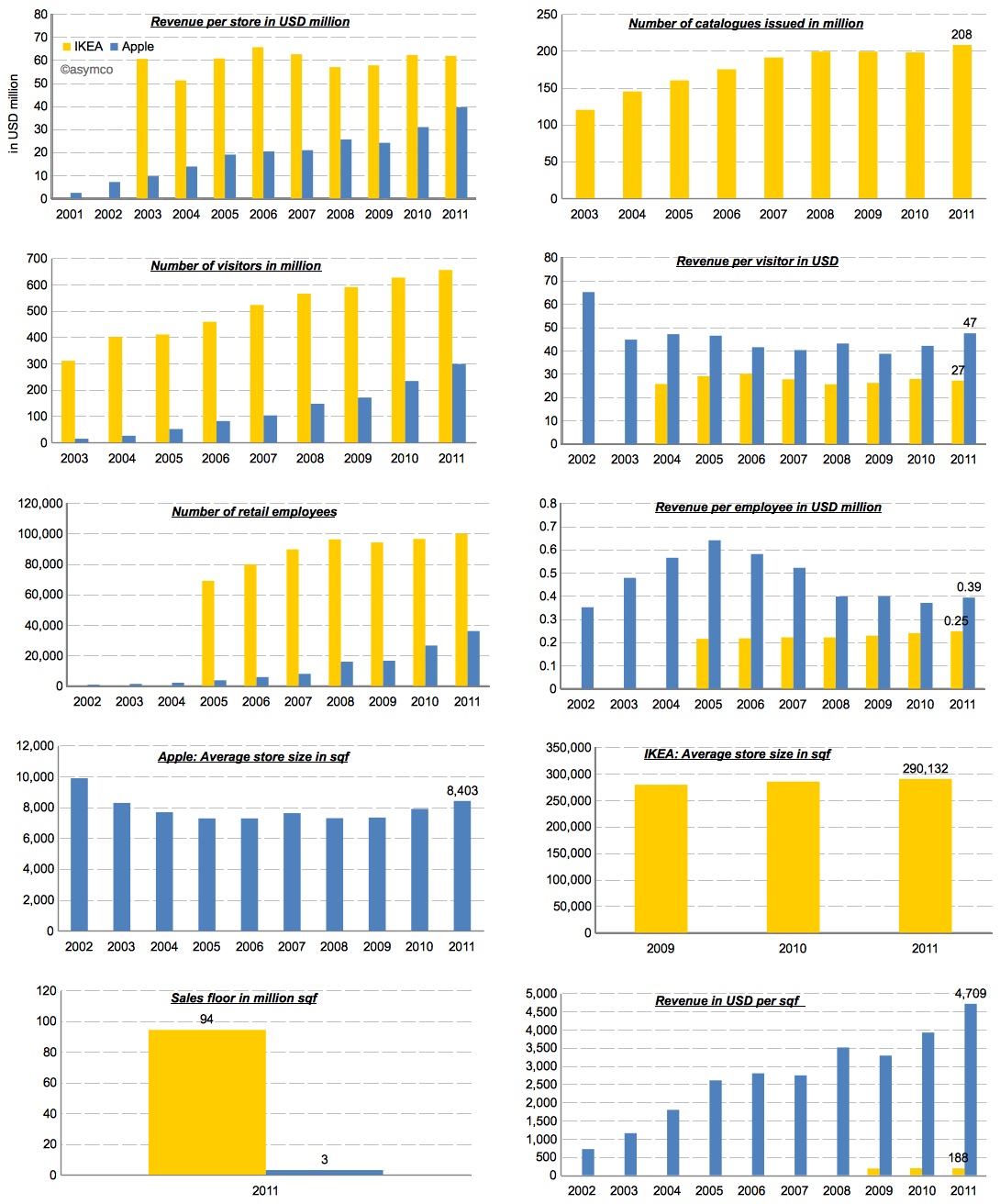

While Apple’s revenue per store is still growing, IKEA’s business seems more mature and stable. This makes sense because furniture prices are stable and the number of products (SKUs) depends on available area per store which cannot grow. Apple on the other hand is limited only by traffic issues. Its products take little space and can even be stored off-site.

Speaking of traffic, with 655 million visitors in 2011, IKEA had more than twice as many visitors in its stores compared to Apple. However, each visitor spent about $27, while Apple’s store visitors purchased for almost twice as much.

The same story applies in employee productivity. IKEA has three times the number of retail employees, but Apple’s revenue per employee are 1.5x bigger than IKEA’s.

The largest difference is in the efficiency of real estate. In terms of total sales area IKEA’s operations have more than 30 times the sales floor of Apple.

As much as these numbers tell a story, they don’t help us understand the cause of success. The two companies have completely different operations and their metrics seem at odds to one another. What works for one could never be applied to the other.

The fact is that there is no magic economic formula for disruptive retail. For example, by measure of sales per square foot, IKEA would not even make the top 20 list of US retailers.

However, there is one major thing they have in common: a clear formula for positioning your retail operations. Both operations are positioned around a job-to-be-done that has a high priority in people’s life. As mentioned in the opening quote, In IKEA’s case it is “I need to furnish my apartment (or this room) today” and in Apple’s case Tim Cook said it best:

“Our retail stores provide the best buying experience and the best customer service anywhere. And while that’s important for a buyer of a Macintosh, in some ways it’s even more important for a buyer of an iPad or an iPhone or another post-PC device because these devices are new to many people. There needs to be a place to discover them, to learn about them before they are purchased, and learn how to get the most out of them after they’re purchased.” Tim Cook, March 2012

Apple offers a place where people can discover and get answers about technology without the pressure of making a purchase. The job is to simplify that which is complex for a price premium.

IKEA offers a place where people can get exactly what they need exactly when they need it. The only downside is that “some assembly is required”. In a way, their job is to introduce some complexity in exchange for convenience and a discount.

In the end, they both get the job done and are amply rewarded for it.

—

Notes:

- Including 13 in Russia.

- The acquisition of UK-based furniture retailer Habitat in 1992 is the only exception.

Discover more from Asymco

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.