Samsung has been selling smartphones for a relatively short time. Although the company sold Windows Mobile, Linux and PalmOS during the last decade, it did not gain significant volumes until it began selling Android phones in 2010 with strong operator support.

That support was substantial in the US. The company crashed the Android party in mid 2010 with its Galaxy brand. Trial evidence reveals that the sales level for Galaxy S1 series phones burst out of the gate taking Samsung from 90k units to 2.5 million units in one quarter.

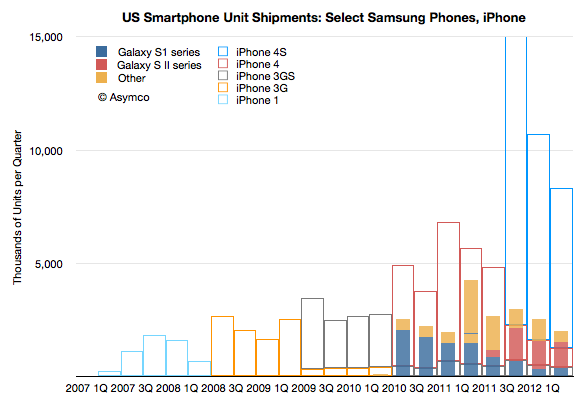

The following graph shows the unit shipments recorded by Samsung for a set of US smartphones.

Note that the profile of sales volume shows a cyclicality with respect to product launches. Each new generation overlaps with previous generations and “fills in” while the older generation product tails off in sales. This is standard portfolio strategy. It also shows the cycle time of launches is approximately four quarters. As the S1 was four quarters old, the SII launched and the SIII follows after four quarters of SII.

What is surprising is that the overall sales volume is not growing. At least for the products catalogued (which exclude the Note) growth for the last four quarters has been: 5%, 34%, 31%, -53%. These are in stark contrast to the iPhone pattern shown in the outline bars behind Samsung’s.

The iPhone ramped slowly in 2007 and 2008 and has been showing remarkable generational growth.

Perhaps it’s still early and Samsung SIII product will ramp up as the contemporary iPhones do, but if it doesn’t we have entertain the possibility that the iPhone does not compete along the same basis.

What does it mean to compete on a different basis?

The basis of competition is the aspect of an offering for which a customer is willing to pay a premium price. It’s hard to know (or to put your finger on) what the basis actually is, but we can test whether it’s the same by measuring whether two products capture prices the same way. If one product that seems to resemble another can obtain price advantage consistently, then perhaps it’s being bought for a different reason.

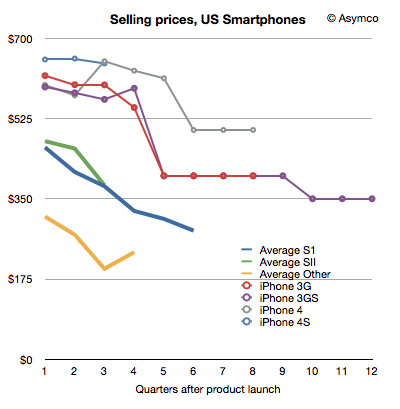

To test this, I produced the following chart showing the prices that Samsung’s phones have been able to capture through their lifetimes; and the same for the iPhone.

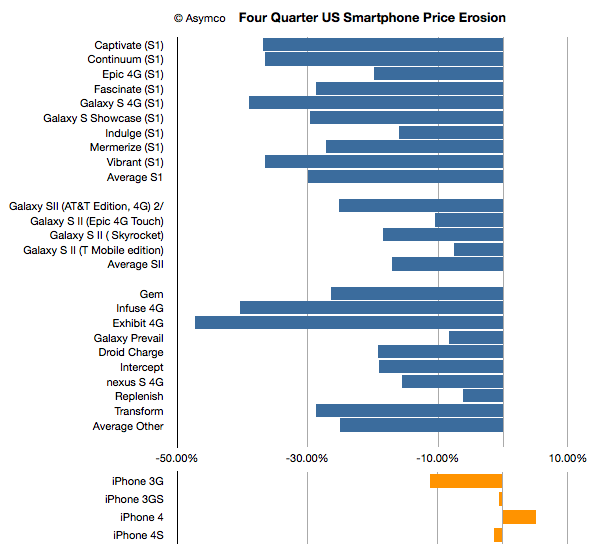

I’ve narrowed the analysis to the first four quarters and summarized the price erosion across all the products as well:

[Note: iPhone 4S, Skyrocket, T-Mobile Galaxy SII showing only three quarters]

As mentioned, it’s still early perhaps, but the pattern for the iPhone has been different.

Samsung’s pattern is not unusual. I’ve seen similar pattern for almost all Nokia products. Prices drop. It’s a standard industry phenomenon.

Therefore the question is not perhaps what is Samsung’s basis of competition: it’s the same as the overall phone industry. The question is what is the basis of competition for the iPhone.

Discover more from Asymco

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.