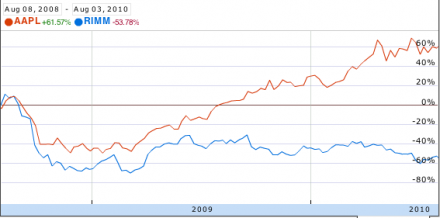

Pricing is a leading indicator of value. Some might argue price and value are often out of whack but, in the long term the two converge.

So it’s instructive to measure how a vendor creates value by what it’s able to charge for its goods. In the case of mobile phones, price is summarized by something called ASP (average selling price) which is measured each quarter across a vendor’s entire portfolio.

Again, there might be local fluctuations, but the trend is your friend here.

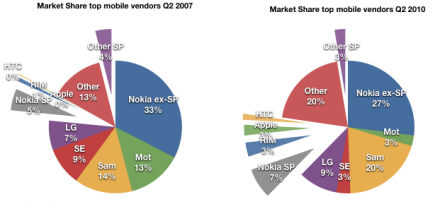

Take a look at these charts I prepared based on the group of seven vendors I previously analyzed in terms of their sales and volume performance.

First, a history of pricing since Q2 2007. All figures are in US dollars current as of time of reporting.

Continue reading “Is an iPhone worth 8 Nokia phones or 2 Blackberries?”