I think Lisa Jackson’s presentation at the September 2018 iPhone launch event was perhaps the most interesting and most profound.

Lisa Jackson is Apple’s vice president of Environment, Policy and Social Initiatives. Previously, Ms. Jackson served as Administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In her role at Apple she has been responsible for the transition to 100% renewable energy use by Apple across all its facilities.

This goal has been achieved and it’s a remarkable achievement deserving congratulations. But her presentation was noteworthy for setting a new goal.

She laid out a goal for Apple to eliminate the need to mine new materials from the Earth.

She said that to reach that goal Apple will have to do three things:

- Sourcing recycled or renewable materials for all products.

- Ensure that Apple products last as long as possible.

- After a long life of use, ensure that they are recycled properly.

It’s this second point that I thought would bring the house down.

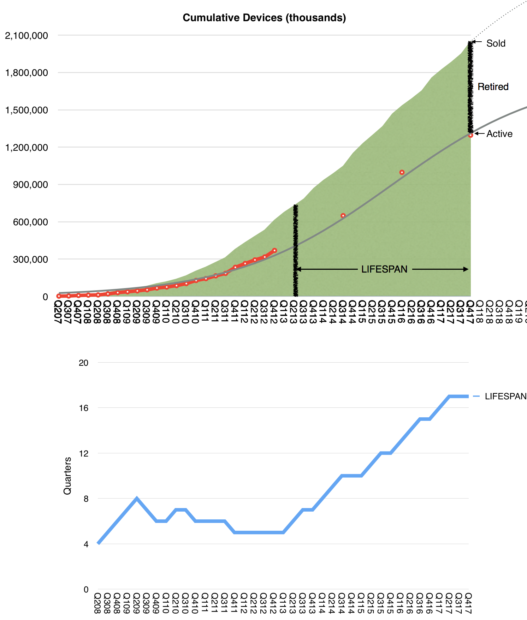

To emphasize the second point she said Apple now strives to design and build durable products that last as long as possible. That means long-lasting hardware coupled with long-lasting software. She pointed out that iOS 12 runs even on iPhone 5S, now five years old. Because iPhones last longer, you can keep using them or pass them on to someone who will continue to use them after you upgrade.

She said that “keeping iPhones in use” is the best thing for the planet.

At this point in the presentation I wondered if everyone would rush out of the room and call their broker to sell Apple shares. One premise of investing in durable goods hardware companies is that value depends on frequency of upgrades. If products are not replaced frequently they do not generate revenues and the company selling them ends up growing very slowly if at all after markets saturate. The smartphone business is certainly approaching saturation and the implication of making Apple products more durable would imply lower revenues from replacements. This anxiety around replacement rates and extended lives is used by analysts to discount future cash flows and if those lifespans are extended price targets come down.

So why would Apple want to do this? What is the logic of this durability focus as a business model? It may be good for the environment but is it good for the bottom line?

Of course, there would be not much business without an environment and we should all strive for sustainability. But this is an existential observation, and it’s defensive. The important call to make is that Apple is making a bet that sustainability is a growth business.

Fundamentally, Apple is betting on having customers not selling them products.

The purpose of Apple as a firm is to create and preserve customers and to create and preserve products. This is fundamental and not fully recognized.

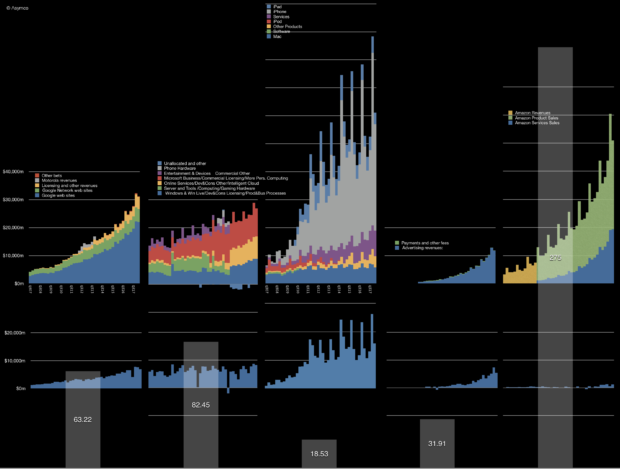

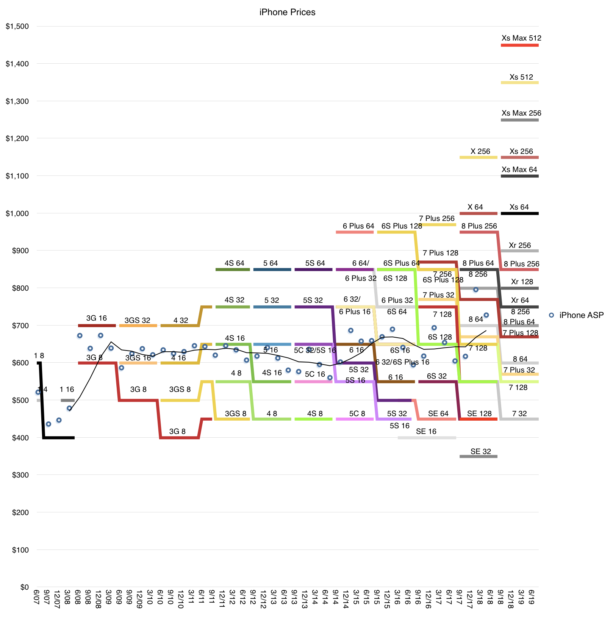

To understand how this works, if you look at the pricing graph below, you can read it as a story of increasing prices for a decreasing market share. But if you understand that each advance in products increases absorbable1 utility then the cost per use remains steady or declines.

An iPhone at $1200 may be less expensive than an iPhone at $600 if the $1200 version lasts twice as long as is used twice as much each day. The $1200 phone delivers 4x the utility at twice the price, making it half the price. By making more durable products, both in terms of hardware and software, the customer base is satisfied and preserved.

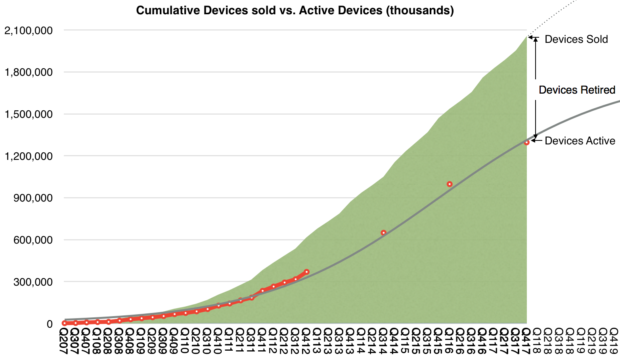

Practically, the initial buyer may resell the iPhone and that 2nd hand devices may be sold yet again. This means an iPhone could have three users over its life and thus it could end up expanding the audience for Apple by a factor of 2 or even 3.

The expanded audience is offered accessories, additional products such as wearables and, of course, services. These residual business models are certainly profitable, perhaps even more so than the iPhone.

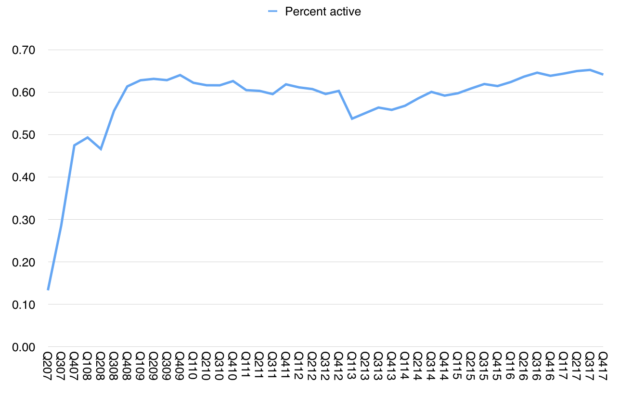

Overall Apple has 1.3 billion devices in use and perhaps as many as 1 billion users. This base is certain to expand and it will expand more rapidly with durable devices and software.

This is a hardware-as-platform and hardware-as-subscription model that no other hardware company can match. It is not only highly responsible but it’s highly defensible and therefore a great business. Planned obsolescence is a bad business and is not defensible.

Therefore the statement that Apple now prioritizes device and software longevity is very important and I consider it one of the most important statements made during the 2018 iPhone launch event.

- Insoluble utility is very dangerous and it’s important to qualify e.g. higher storage capacity that people hunger for or better cameras that increase picture taking from features that are neat but don’t get utilized [↩]