The saga of Nokia’s challenges has been well documented in this weblog.

For this quarter, we take a look at the sequential deterioration in Nokia’s bottom line and draw causal inferences to its lack of competitiveness in mobile operating systems.

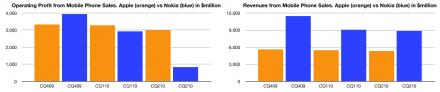

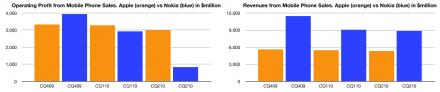

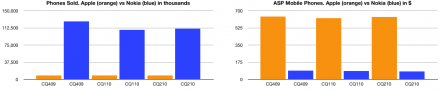

First, the bottom and top lines are shown below (in blue) and compared with Apple (in orange):

The charts show how Nokia’s bottom line (left) collapsed while the top line (right) remained relatively solid. By comparison, Apple remained consistent in revenue with slight dip in profit as it transitioned to a new model.

The charts show how Nokia’s bottom line (left) collapsed while the top line (right) remained relatively solid. By comparison, Apple remained consistent in revenue with slight dip in profit as it transitioned to a new model.

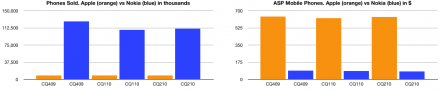

The top line (sales) is the product of units sold and their average selling price (ASP). Here are these two quantities side-by-side:

Note how Apple’s units are hard to discern relative to Nokia’s volume and how the opposite is true for the selling price. These values include all phones sold by the companies.

Note how Apple’s units are hard to discern relative to Nokia’s volume and how the opposite is true for the selling price. These values include all phones sold by the companies.

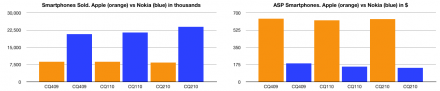

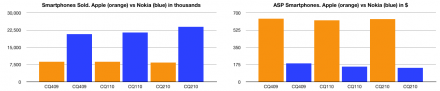

The story is a bit more clear when comparing the smartphone part of Nokia’s business, again with units and ASP:

The story here is telling: even in smartphones, Apple’s ASP is dramatically higher and much more resilient.

The story here is telling: even in smartphones, Apple’s ASP is dramatically higher and much more resilient.

The question has to be why: Why can Apple retain not only higher prices (and hence margins)? The answer is competitiveness. Margin is an indication of value created and value differential is competitive differentiation. All the user satisfaction surveys, the reviews and tests boil down to these hard numbers above. The deterioration of Nokia’s business is directly traceable to its historic failure to embrace mobile software as a disruptive force and instead using it to sustain a hardware business.