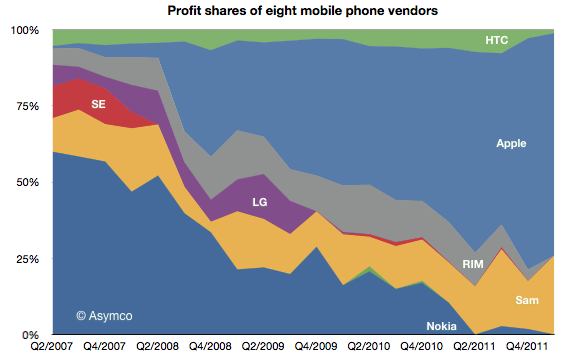

“Clearly this stuff isn’t selling,” said Monga [an analyst at Veritas Investments Research in Toronto.]…

RIM took a $485 million pretax charge to write down the value of its PlayBook inventory in December, after shipping just 150,000 of the tablet computers in the quarter. Then in March, the company recorded a $267 million expense for BlackBerry inventory. RIM said at the time that it would stop giving sales and profit guidance because of “ongoing weakness” in the U.S.

via RIM Writedown Risked With $1 Billion Inventory: Corporate Canada – Businessweek.

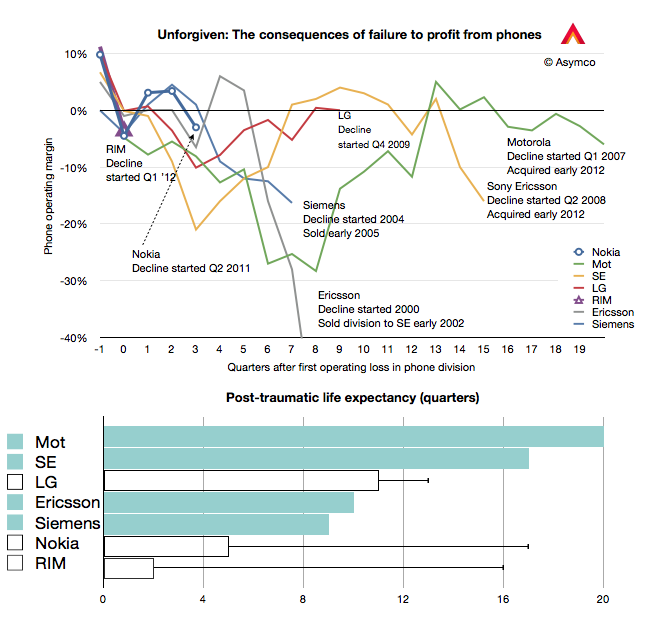

RIM has just entered what I call the Post-traumatic period of a phone maker’s life. This period is defined as beginning with a loss-making quarter and ending with the company’s exit from the business. These post-traumatic periods were visualized first here and the pattern was first discussed about a year ago here.

I’ve updated the chart with the current data and added the bar chart below to illustrated the “post-traumatic life expectancy” for the companies shown. Companies still operating are shown with bars without color while companies that have exited are shown with solid color bars. Continue reading “Post-traumatic life expectancy of phone vendors”