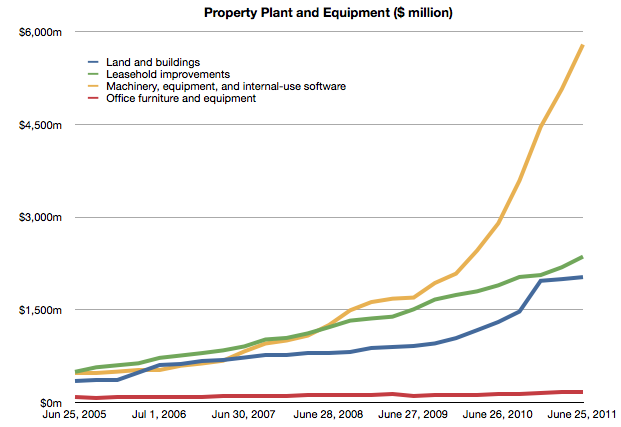

In his recent posts Horace took a look at Apple’s fixed assets and their development over the recent years. He also tested the hypotheses that Apple is making investments into machinery & equipment on which iOS devices are produced by overlaying iOS volumes with preceding changes in property, plant and equipment (PP&E).

The question that has arisen is: Are Apple’s investments in PP&E extraordinary?

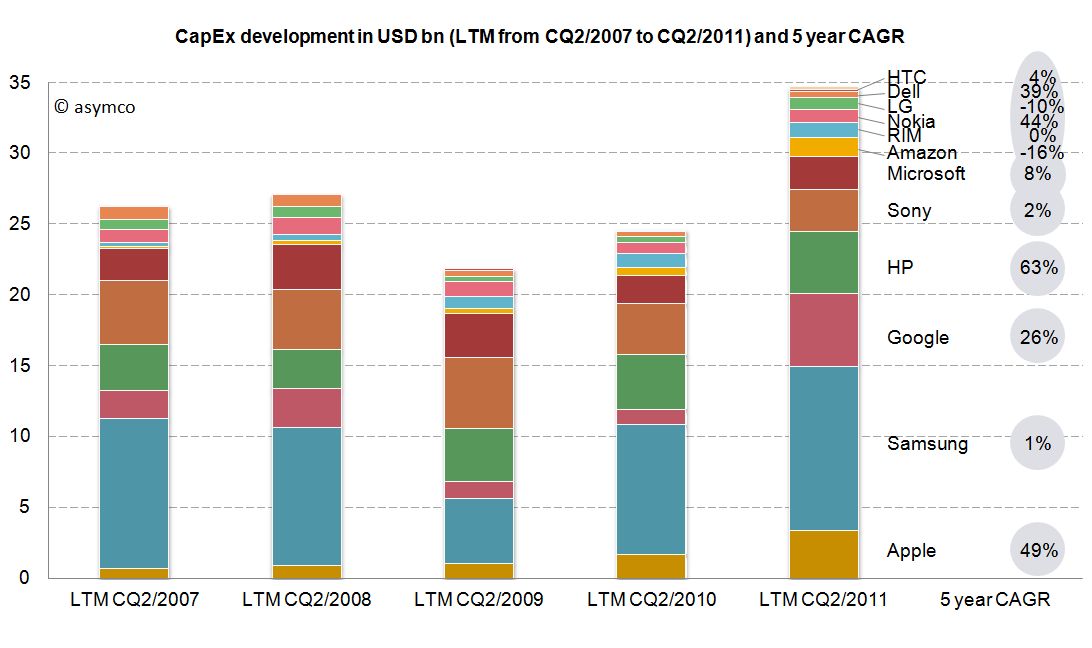

To answer, I have compiled the capital expenditures (CapEx) for our previously established peer group [1].

But first we need to clarify what CapEx include and not include. CapEx includes investment into property, plants, equipment, office furniture, larger IT hardware and in some cases patents; CapEx do not include investment into long-term marketable securities or other long-term financial instruments, acquisitions or capitalized R&D. Furthermore, CapEx are gross values and are not net of any sold equipment [2]. CapEx are largely depending on a company’s business model and strategy. For example if you are a manufacturer you need equipment to operate, if you are a software company or a retailer, your business will not be capital intensive.

As the second calendar quarter of 2011 is the latest quarter for which all companies have reported figures, we will take a look at last twelve months’ (LTM) figures from Q2/2011 backwards. The following stacked bar chart shows the combined CapEx of our peer group:

The combined capital expenditures of our peer group for the Continue reading “Are Apple’s investments in PP&E extraordinary?”