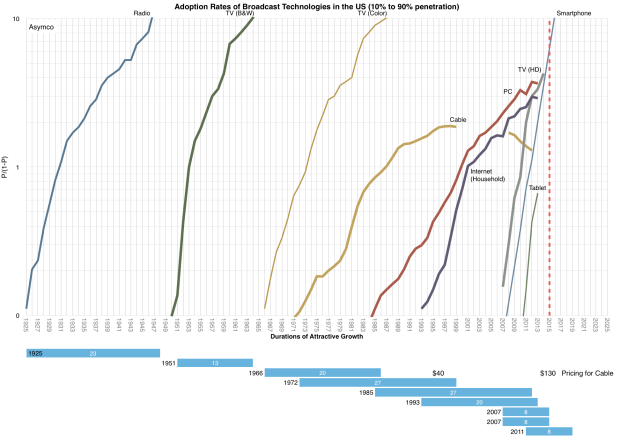

Paying for TV has been a curious consumer phenomenon. There was a time when TV was free to consumers. It was delivered as a broadcast over-the-air and paid for either by commercials (US mostly) or by taxes on viewers (Europe mostly). The consumers were delighted with the idea as it was far better than radio and radio was delightful because it was far better than no radio.

The process of convincing consumers to pay for something that used to be free was quite interesting. The first benefit to be articulated was that the quality of the picture would be much better. It would, in essence, be noise-free.1

The second benefit was an increase in the number of channels. VHF and UHF television would cover about three and 5 channels respectively while cable could offer dozens, many specializing on specific types of content like the Home Box Office (HBO) offering movies and ESPN offering sports only and MTV music videos and CNN news only.

The third benefit was fewer (or no) commercials for some of the channels. This was especially valued by fans of movies whose interruption by commercials was often detracting from the immersive value and continuity of the cinematic experience.

These benefits were very attractive during the 1980s, to the extent that about 60% of US households adopted cable. An additional group later adopted satellite-based pay-TV as the technology became reasonably cheap.

These benefits were priced modestly but as the quality and breadth of programming increased, prices rose. An average cable bill of $40/month in 1995 is $130 today2. Some of that revenue went into upgrading the capital equipment in use (the plant) and some into paying for the higher production values. Yet more went to the sports leagues and their players whose business models increasingly depended on broadcast rights.

These benefits were priced modestly but as the quality and breadth of programming increased, prices rose. An average cable bill of $40/month in 1995 is $130 today2. Some of that revenue went into upgrading the capital equipment in use (the plant) and some into paying for the higher production values. Yet more went to the sports leagues and their players whose business models increasingly depended on broadcast rights.