The mobile phone market is intertwined with the telecommunications industry which is vast and there are numerous competitors which are much more dynamic and better capitalized than the moribund PC or music player vendors. It’s also a regulated and fragmented global market with 1.2 billion units and 5 billion consumers—far greater than any of the markets Apple played in for its first 30 years.

Nevertheless, the iPhone has had a huge impact on the industry. To show just how much of an impact, I dove in and pulled over 500 data points on three years’ financial performance of seven competitors responsible for 80 percent of units being shipped today. The time frame covers the iPhone’s participation in the market so it allows for “before-and-after” comparisons.

I divided the findings into five articles:

- Unit Volumes. The evolution of market share.

- Revenues. The shift in where dollars are spent.

- Selling prices. The tale of ASP erosion.

- Operating margin. Profitability ratios over time.

Now I turn my attention to draw a bottom line from all the data above, namely the operating earnings (EBIT or Earnings before Interest and Taxation).

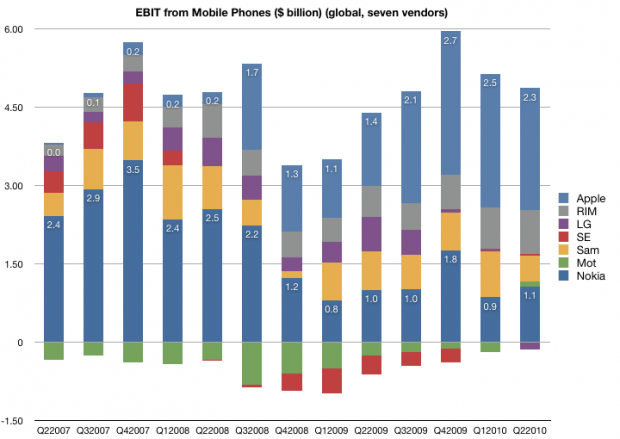

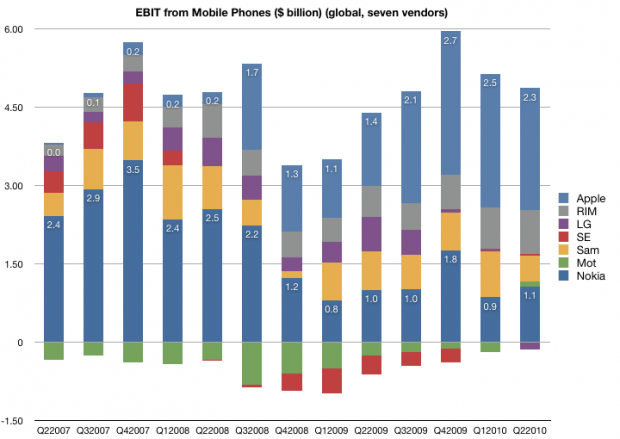

The first chart shows the EBIT from the top seven vendors of mobile phones since the quarter when the iPhone launched. I annotated Nokia and Apple’s bars to give perspective.

The total available profits in the industry dipped to a bit under $4 billion at the trough of the recession, and have recovered to nearly $6 billion in the holiday quarter last year. However, not all vendors are profitable. As you might expect from looking at the operating margins, Motorola and Sony Ericsson have been generating losses for most of this time period. They have both reached profitability in the last quarter, though at very low levels and after having lost a large part of their sales. LG has turned negative this past quarter after being a modest earner for some time. Samsung has maintained a fairly even consistency in its profit capture, though with its expanding market share, it seems to have come at the cost of pricing.

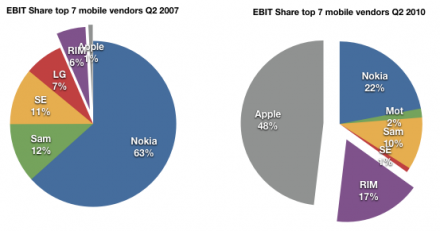

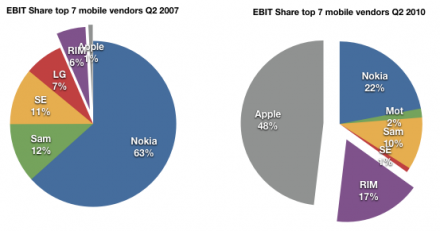

Finally, looking at the pure smartphone vendors RIM and Apple, the picture is nothing short of astonishing. This before-and-after share-of-available-profit chart shows that the two entrants went from about 7% profit share to 65% in three years.

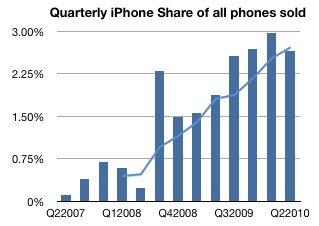

Apple in particular is capturing about half of the available profits with three percent of the units. It dwarfs all the other vendors, more than double the nearest (Nokia). All that in three years and with the added burdens of only three models, a recession and limited distribution.

What does it all mean?

Here are my conclusions, enumerated:

- The lack of a real response. The recurring theme in this series of articles has been that giant multinational incumbents in a vast and rapidly growing industry, enjoying all the advantages that size and incumbency, have had their profits taken from them. And they don’t seem to have put up much of a fight.

- It’s all wealth transfer. Note the total amount of profit available has not increased markedly; this is not about incumbents growing the pie. Two thirds of what should have rightly been theirs moved from the incumbent shareholders to the entrant shareholders.

- Speed. This shift of profit occurred over an unprecedentedly short period of time. Three years is no more than two product cycles in the industry and it’s an order of magnitude faster than what happened historically to other industries.

- Disruption is the diagnosis here. The incumbents were caught in the headlights. Disruptive innovation leads to asymmetric competition and this is what we just witnessed. History has shown that the shift of profits is usually the last stage of disruption and is usually irreversible because the change in business models cannot happen at the rate of change of profit transfer.

Which leads me to one final point.

When analyzing the potential for challengers to the new winners, the most cited is Android. Can Android affect this redistribution of profit once again? And to whom?

If Android is to become the dominant platform, does it depend on the success of its licensees? Who are these licensees and what are the chances that they will be able to align their businesses to what Android offers (a new revenue model based on services and advertising).

One problem I see is that Google is making a bet on those same vendors who are now squeezed in the middle of that last pie chart: Samsung, LG, Motorola and Sony Ericsson. Nokia, Apple and RIM will certainly not take the OS over what they already have as it dilutes their differentiation and margins. That means Android is aligned with the biggest losers in the industry.

So how likely are these disrupted ex-giants to recover and take Android forward? My bet: slim to none. Android does not offer more than a lifeline. It is not a foundation for long-term profitability as it presumes the profits accrue to the network and possibly to Google. Profit evaporation out of devices to Google may be a possibility at some time in the future, but only if the devices don’t need too much attention to remain competitive. But because they’re still not good enough (and they won’t be for years to come), it’s certain that attention to detail is what will be most important to stay abreast of Apple.[1]

So here we have the real challenge to Android: partnership with defeated incumbents whose ability to build profitable and differentiated products is hamstrung by the licensing model and whose incentives to move up the steep trajectory of necessary improvements are limited.

In other words, Android’s licensees won’t have the profits or the motivation to spend on R&D so as to make exceptionally competitive products at a time when being competitive is what matters most.

[1]: I would argue the same lack of symmetry with licensed software vendor Microsoft is what led the the failure of the same incumbents to make a dent in the industry with Windows Mobile [2003 to 2010].

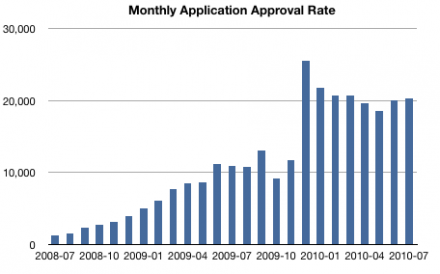

The 20k/month has been steady during the last 7 months so I think the last 4k apps will be added in the next week, making the 300k roll-over in August, as forecast. The approval rate did not accelerate however but stayed pretty steady. There was a similar plateau in the middle of last year around 10k apps/month.

The 20k/month has been steady during the last 7 months so I think the last 4k apps will be added in the next week, making the 300k roll-over in August, as forecast. The approval rate did not accelerate however but stayed pretty steady. There was a similar plateau in the middle of last year around 10k apps/month.