The App Store is almost 9 years old. In that time it has generated about $100 billion in revenues, of which about $70 billion has been passed on to developers and $30 billion was kept by Apple. It’s very likely that running the App Store for 9 years did not cost $30 billion so, if it were an independent “business unit” it would probably have been and still be quite profitable.

But Apple does not run “business units” with separate Profit and Loss statements. The App Store is a part of Services which is an amalgamation of non-hardware sources of revenues but that does not mean it’s a business. The purpose of Services isn’t to turn a profit or define its value through some metric of financial performance.

The purpose of Services is to make the experience for the Apple user better. The combination of good experiences allows Apple to be perceived as a valuable brand and that allows it to obtain consistently above-average profitability through pricing power. I like to emphasize that the iPhone at over $600 in average price is more than twice the average price of all the other smartphones and captures over 90% of all available profits.

This is something that remains after a decade and indeed the price is rising in the face of overall price erosion, all without a decrease in volumes. The sustainability of this exceptionalism is due to no one single thing. It’s due to the persistence across all the things Apple does: product, stores, software and services and many other details too numerous to count.

The result is a large and expanding base of satisfied customers and a large and expanding base of partners both in hardware and software and services. The WWDC event this year showed how the ecosystem of Apple is booming with over 3 million new developers and Keynote screenfuls of partnerships. All this makes for a complex picture but it’s a real picture.

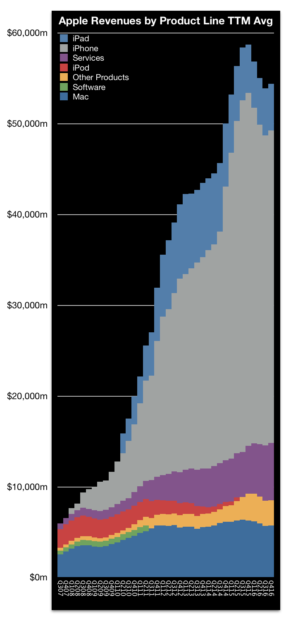

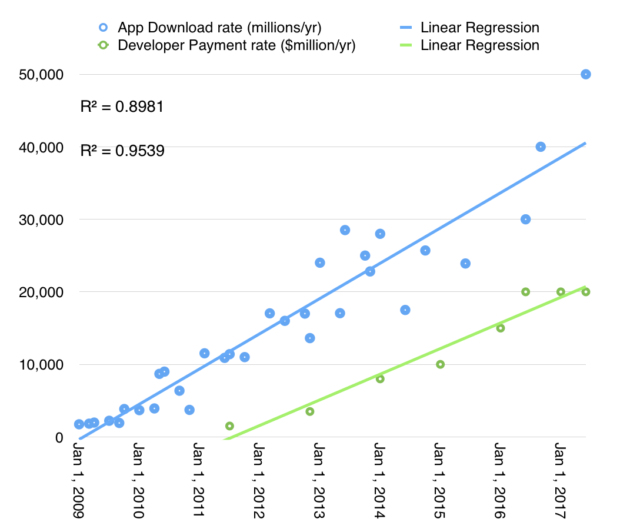

The latest numbers on Services try to tell this story: 180 billion App downloads from 500 million App store weekly visitors. The download rate is accelerating as shown in the following graph:

The revenue or payment rates can also be shown as accelerating though at a different rate. In both cases, the story of apps is not yet over, regardless of commentary to the contrary. Much of this growth comes from new markets like China and as India joins the iOS world, there is yet more opportunity emerging.

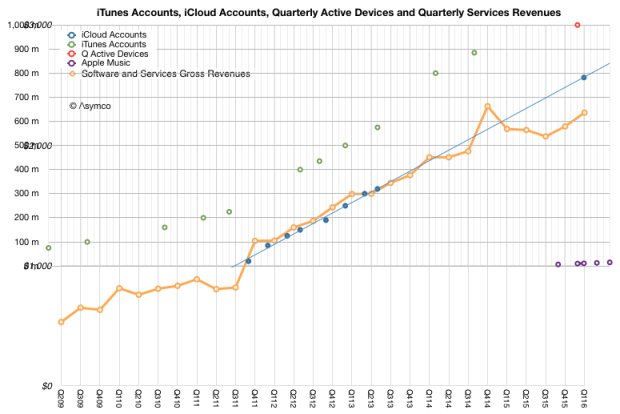

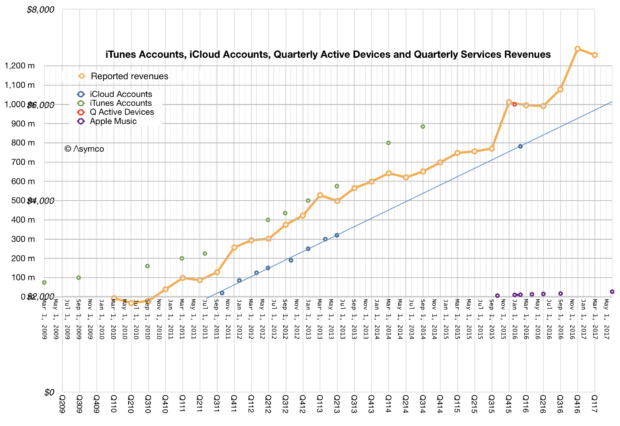

This enables part of the story of Services which can be tracked with several other metrics: reported revenues, iCloud accounts, active devices, and iTunes accounts are highly correlated.

The patterns after a decade are remarkably consistent. One would have thought that with mobile saturation in advanced markets, the content story would be told through horizontal lines. What we still see is the same slopes we’ve seen since the earliest days.

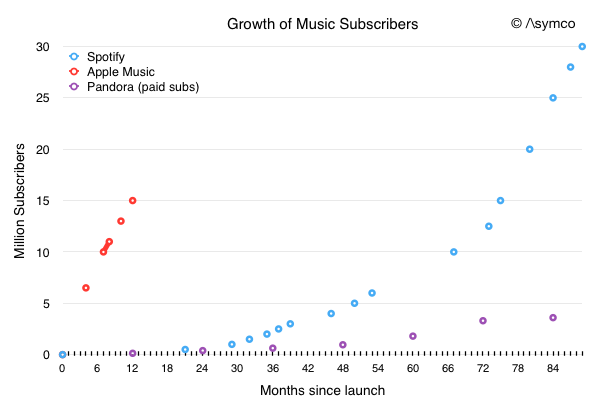

But the biggest story at WWDC was the re-design of the App Store as a curated content market. The changes are profound: discovery, curation and the surfacing of content have been revamped. It’s hard to predict the implications of this but one of the indications of direction was the separation of “Games” from “Apps”. This is a jarring idea since if all Apps are content, what makes Games different from other Apps? Is this a genre elevated to a new medium?

I can’t yet get a sense of where this is heading, if anywhere, but the remarkable story of Apps is that it’s still an ongoing story. We may be on chapter 2 and we can’t predict how many chapters remain.

Keep an eye on Apps and Services and developers. They are not lagging indicators of success for Apple. They are very much leading.