Understanding Apple’s intentions seems to be a popular parlor game and there are many attempts at divining intention from data and market study. These attempts at market research for answers are futile because Apple does not compete in existing markets but rather it creates new markets. For instance, the market for the Apple II could not have been assessed from research into the computing market of 1974. The intention for Apple to enter into music devices and services could not have been predicted through an analysis of MP3 player market in 2000. The iPhone was also not predicated on the market for “Internet Communicators” in 2006 or 2002 when the iPad was first contemplated.

Instead of measuring the size of pre-existing markets, surveying the functionality of existing products, or weighing toxically financialized ratios like margins and market shares, I recall this ad (Our Signature, first seen at 2013 WWDC):

This is it

This is what matters

The experience of a product

How it will make someone feel

Will it make life better?

Does it deserve to exist?

We spend a lot of time on a few great things

Until every idea we touch

Enhances each life it touches

You may rarely look at it

But you will always feel it

This is our signature

And it means everything

My interpretation of these lines, coupled with additional public statements can be used to create a “litmus test” for new product categories:

1. The experience of a product. Read: They will work on things to which they can make a meaningful contribution. To me this means that they will build things which require an integrated approach. As Apple is “the last integrated company standing” it means they will work on problems where the system is not good enough. This means that they will not work on problems where an individual modular component is not good enough. By system I mean, in the largest sense: production, design, distribution, sales, support and services must work in a seamless way. Systems analysis implies a broad understanding of the causes of insufficient performance along the dimensions of “experience”. The experiences are what differentiate the products (and lead to high margins) and these experiences are possible only through the control of interdependent modules.

2. Does it deserve to exist? Read: They will work on very few things. They will say no to many things. It’s still true that all of Apple’s products can fit on one table. That may not be true forever, but their product space will not grow as quickly as sales grow. This means that there is no notion of “marginal value” or portfolio theory where products are added because they can be justified as “moving the needle” or balancing demand. Rather, the few things which will be worked on will address non-consumption. Non-consumption of experiences.

3. Enhance life. Read: The things they release are inevitable even though nobody asked for them. The reason this is possible is that there are unmet and unidentified “jobs to be done” which are powerful sources of demand and whose satisfaction leads to unforeseen rewards. The problems that can be addressed are uncovered through a process of conversation with a few people. They are not uncovered through surveys or large n statistical studies. Without the ability to ask the right questions, big data only leads to big misdirection. In contrast, good taste in questions allows small n to lead to big insight. Apple’s ability for finding the right problem to solve comes from this greatness of taste in questions.

So given this litmus test, will Apple build a Car?

I believe the problem of transportation and its proxy, the automobile, provide all the requisite demand for Apple’s attention. Technical questions abound and they may still prove unsurmountable before a launch happens, but there are no doubts in my mind that this is a problem Apple would see fit to address.

Non-consumption of unmet and unarticulated jobs to be done can and should be addressed with systems solutions and new experiences.

The poetry is pretty clear on the matter.

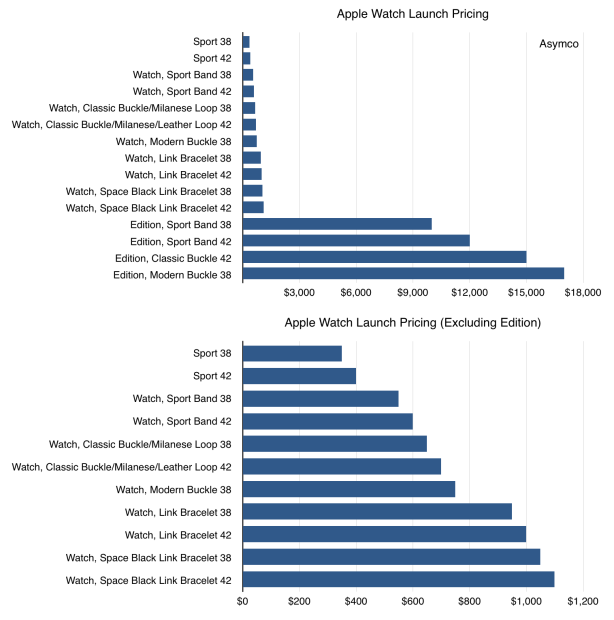

In contrast, the watches are differentiated by size, materials and bands. There are also a total of 38 watch configurations available at launch (SKUs) and another 38 bands that can be purchased separately.

In contrast, the watches are differentiated by size, materials and bands. There are also a total of 38 watch configurations available at launch (SKUs) and another 38 bands that can be purchased separately.