It’s perhaps fitting that an industry that produces illusions is in itself an illusion. The absence of public scrutiny of its finances and business model leads to a lot of myths or misconceptions. Some of these are discussed anecdotally in books and other works[1], but the absence of data makes the anecdotal evidence unsatisfying to an analyst.

What if we could find patterns in data about the industry to confirm or deny these oral histories? Fortunately some data actually exists. There are collections of data about movies released and some of the attributes of these releases such as box office receipts, theaters opening, budgets (sparsely), and distributors. This data is typically used for marketing purposes to celebrate the “hits” and thus entice more people to see the movies.

However, other information can also be obtained through analysis of the data. In fact, a rather compelling story can be told. That’s the purpose of this post. Our story will be expanded over time but this first draft should be enough to allow a discussion to begin. The story is built in four sub-stories:

- Drama / Comedy vs. Adventure / Fantasy: Why the Ancient Greeks had it all wrong.

- The magic of summertime: Market access and school schedules

- The perpetual incumbency: What happens to Hollywood startups

- The Popcorn economy: The peculiar power of theaters in an age of television

These stories were the result of observations in data alone. We have no first-hand knowledge of the industry and have only used basic software tools to seek out patterns in public data[1].

The data set includes approximately 12,000 titles released between 1975 and present with various degree of completeness. Some of these years are not completely populated and some data is undoubtedly in error. However the large sample should offer enough substance for patterns to emerge in spite of this.

Drama / Comedy vs. Adventure / Fantasy: Why the Ancient Greeks had it all wrong

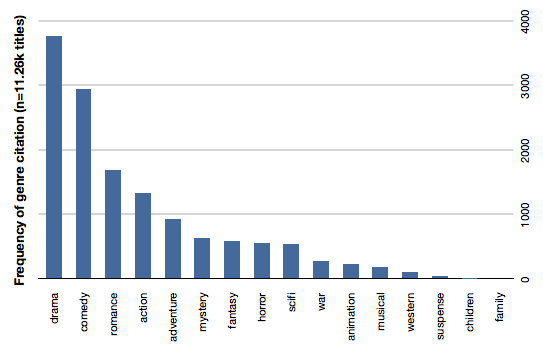

Storytelling has not changed throughout history. The same types of stories affect audiences the same way since stories were first told. The earliest known “genres” were tragedy and comedy and they are still seen as the bedrock of theater today. The same is true for movies. The following bar chart shows the distribution of genres as cited by movies over our data set.  Drama and comedy are about 50% of all movies made. If we add romance they are 60% of cited genres. This is understandable given the history of theater. However the profitability (or revenue potential) of those genres is not as strong as Action, Adventure and Fantasy. The following chart shows the same count of genre citation but only for movies grossing over $200 million (which we chose to call “blockbusters”).

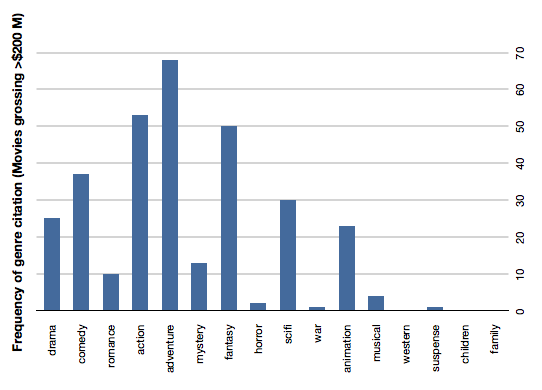

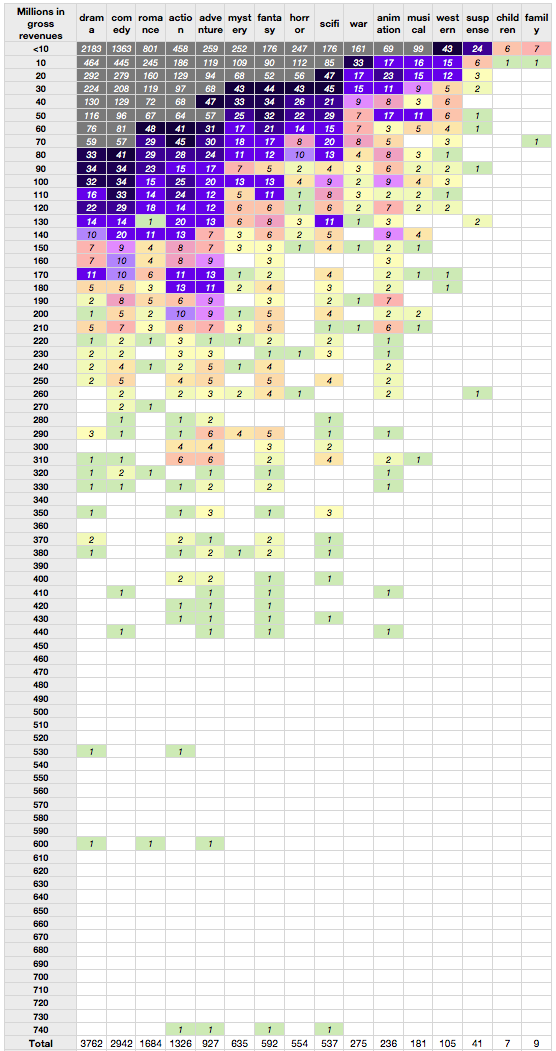

Drama and comedy are about 50% of all movies made. If we add romance they are 60% of cited genres. This is understandable given the history of theater. However the profitability (or revenue potential) of those genres is not as strong as Action, Adventure and Fantasy. The following chart shows the same count of genre citation but only for movies grossing over $200 million (which we chose to call “blockbusters”).  Action, adventure and fantasy handily beat Comedy and even SciFi beats drama. Romance, musicals and and mystery genres typically associated with female audiences are very rarely successful as blockbusters. The overall data is shown in the following table. The rows represent gross revenues and the columns genres cited ranked in order of frequency. One can easily observe the density of low earning drama and comedy (grey colored) vs. the more lucrative instances of fantasy and adventure. These male-dominated genres have consistent success into middle, high and very high revenue tiers.

Action, adventure and fantasy handily beat Comedy and even SciFi beats drama. Romance, musicals and and mystery genres typically associated with female audiences are very rarely successful as blockbusters. The overall data is shown in the following table. The rows represent gross revenues and the columns genres cited ranked in order of frequency. One can easily observe the density of low earning drama and comedy (grey colored) vs. the more lucrative instances of fantasy and adventure. These male-dominated genres have consistent success into middle, high and very high revenue tiers.

The reason for this blockbuster attention to action and adventure is probably the prevailing theater-going audience demographic: adolescent males. The industry still produces the classic genres but less profitably than what the current targeted markets.

Indeed, these genres were very uncommon in eras predating the late 1970s. More “adult-oriented” movies like romance (Gone with the Wind), musicals (The Sound of Music) and epic movies (Ben Hur, The Ten Comandments) were common in the “golden age” of Hollywood. As we’ll see in the next section, the age of the audience is a now driving more than just genre selection.

The magic of summertime: Market access and school schedules

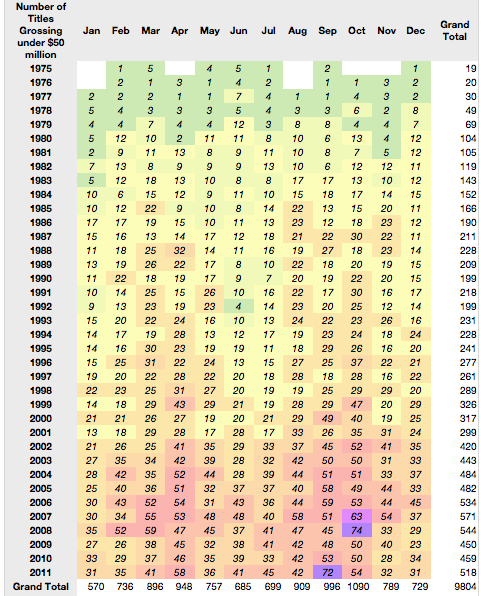

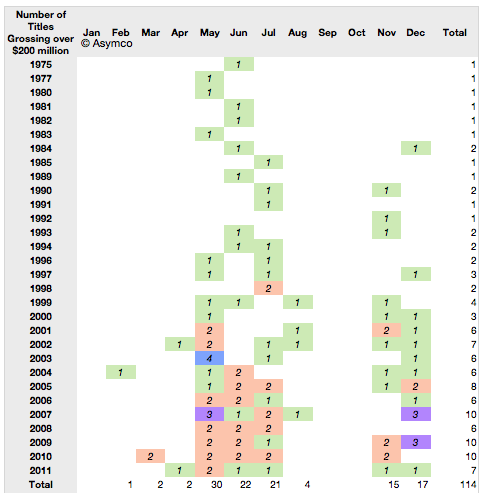

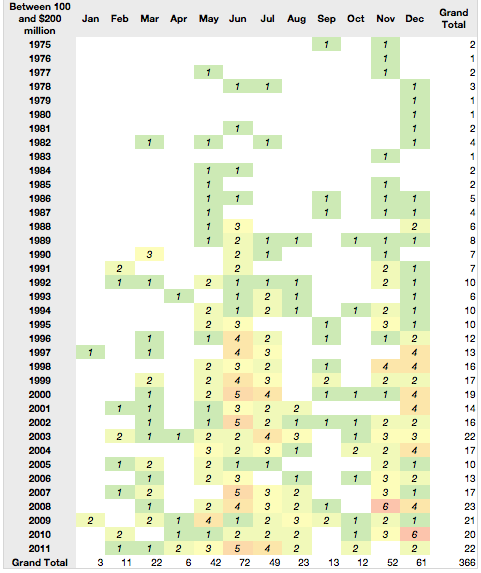

Using the word “Summer” before “Blockbuster” has become almost redundant. What is less understood is that watching movies in the summer is rather a new idea. It started effectively with Jaws in 1975 and ever since major film studios have planned their annual marketing around a summer schedule. There is clear evidence for this in the data. Here is a table showing the blockbuster release months since 1975. (The number of titles grossing over $200 million and the months in which they were released).

The same pattern repeats for the next tier of highly successful movies–those grossing between $100 and $200 million.

But what about the less successful movies? Those earning less than $50 million actually show a counter-success pattern.

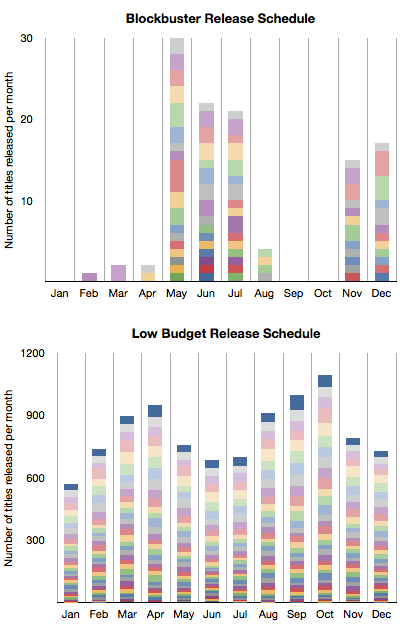

To contrast this further, here is a stacked bar chart comparison between frequency of release by month for the most successful tier vs. the least successful tier (colors represent years with oldest at the bottom).

It would seem that summer and success are in a causal relationship. There is a clear pattern with the only non-summer months having blockbuster releases being November and December.

But there is more to this pattern.

The blockbuster schedule happens to coincide with the school holiday schedule in the US. This again points to the “profitable” audience being school-age children, and mostly male.

The perpetual incumbency: Where are the Hollywood startups?

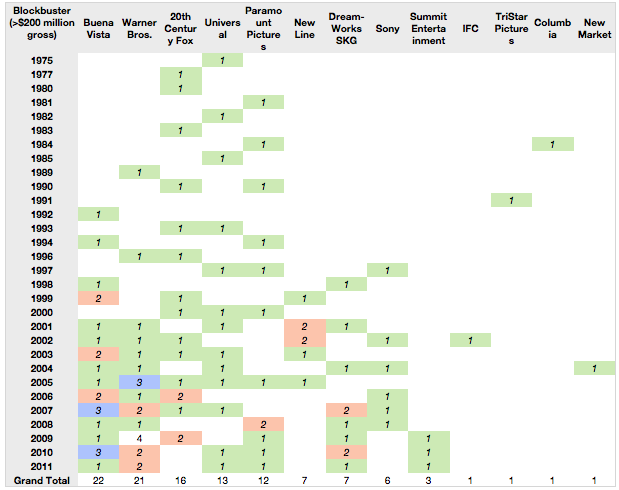

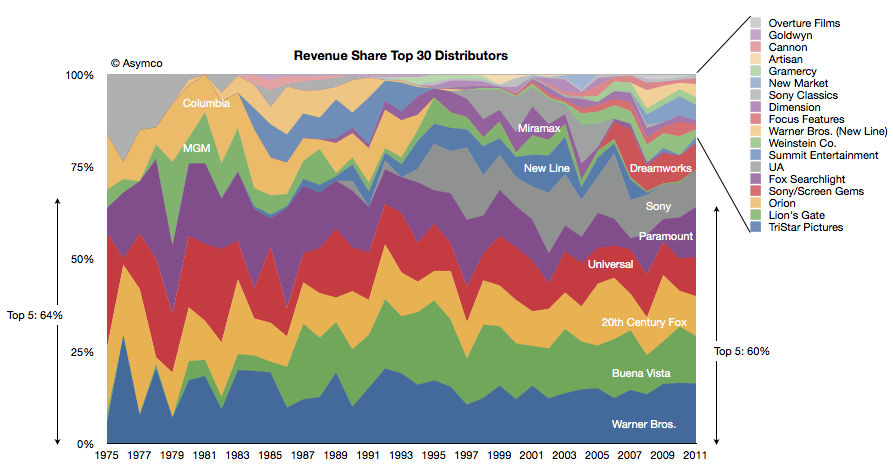

The third observation has to do with the major film studios. We took the box office revenues and allocated them to the studios over time. The following chart shows the share of those revenues for the top 30 studios.  The top five were earning 64% of revenues in 1975 and the top five were earning 60% in 2011. One of the top five from 1975 is no longer in the running this year (MGM) and one new major was added (Buena Vista, owned by Disney).

The top five were earning 64% of revenues in 1975 and the top five were earning 60% in 2011. One of the top five from 1975 is no longer in the running this year (MGM) and one new major was added (Buena Vista, owned by Disney).

There has been one other notable change: Columbia was acquired by Sony but stayed out of the top 5. Beside Disney there is one new significant entrant in Dreamworks gaining share in the last decade.

But the prevailing impression from the data is that the incumbents remained as such during the last four decades. There are many small studios but they have not “disrupted” the market by shifting significant revenues out of the hands of the majors. Indeed the typical strategy seems to be to start a studio with the hope of it being acquired by a major.

Even the entrants are industry insiders: Disney and Dreamworks are not asymmetric in their business models in any way. In fact, when viewing the data by blockbuster creation, the majors feature prominently. There are only a handful of blockbusters from the smaller companies.

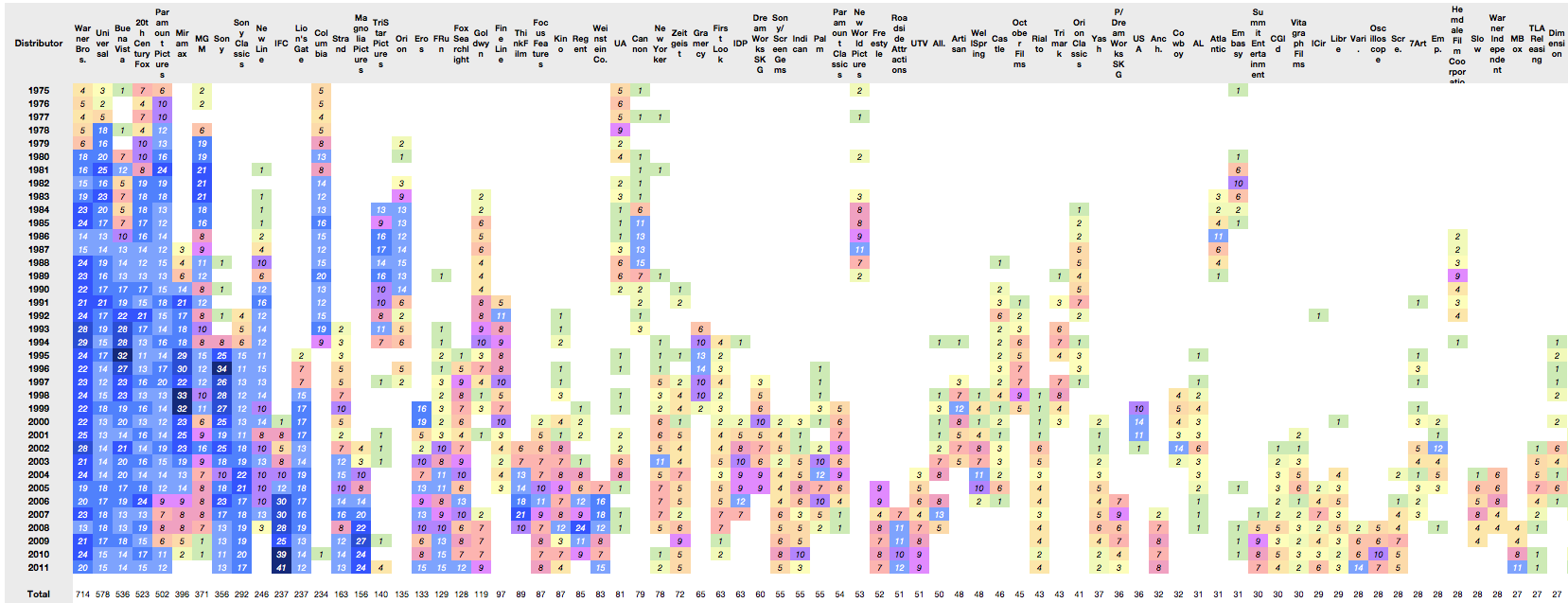

When looking at overall production rates, again the majors (and their subsidiaries) dominate. Here are the top 75 distributors of movies showing nearly 9000 movies (click image for full-size):

The conclusion from this data might be that Hollywood does not change all that much in terms of who makes the money. But that itself is a symptom of a deeper reality: that there is little that changes at all.

We can even perhaps hypothesize that there is no business model innovation taking place. Any such innovation is usually manifested in a reversal of fortunes for incumbents.

But technological change is happening. The following section describes how this appears in the data.

The Popcorn economy: The peculiar power of theaters in an age of television

The data we are sampling (box office gross revenues) is actually a small and shrinking subset of what movies generate. In addition, there are international revenues, media sales (DVD, video tape), TV rights, and merchandise to name a few. But theaters are still an important part of the picture.

Although they make up less than 20% of gross, their importance is disproportionate due to the signal they send other markets about the popularity of a movie. In other words, a movie must first be proven in a US theater before its value is priced by the other channels.

However, this essential theatrical release has changed in one fundamental way. Releases are now geared for larger initial scopes with shorter runs and less dependency on “word of mouth” to increase sales.

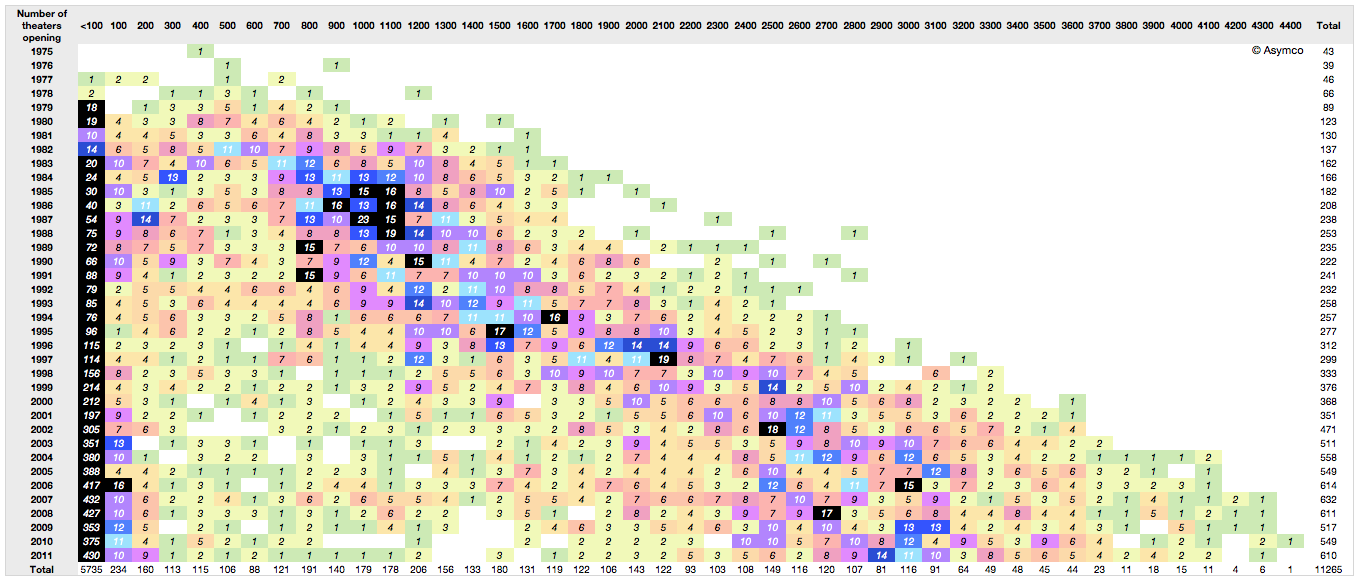

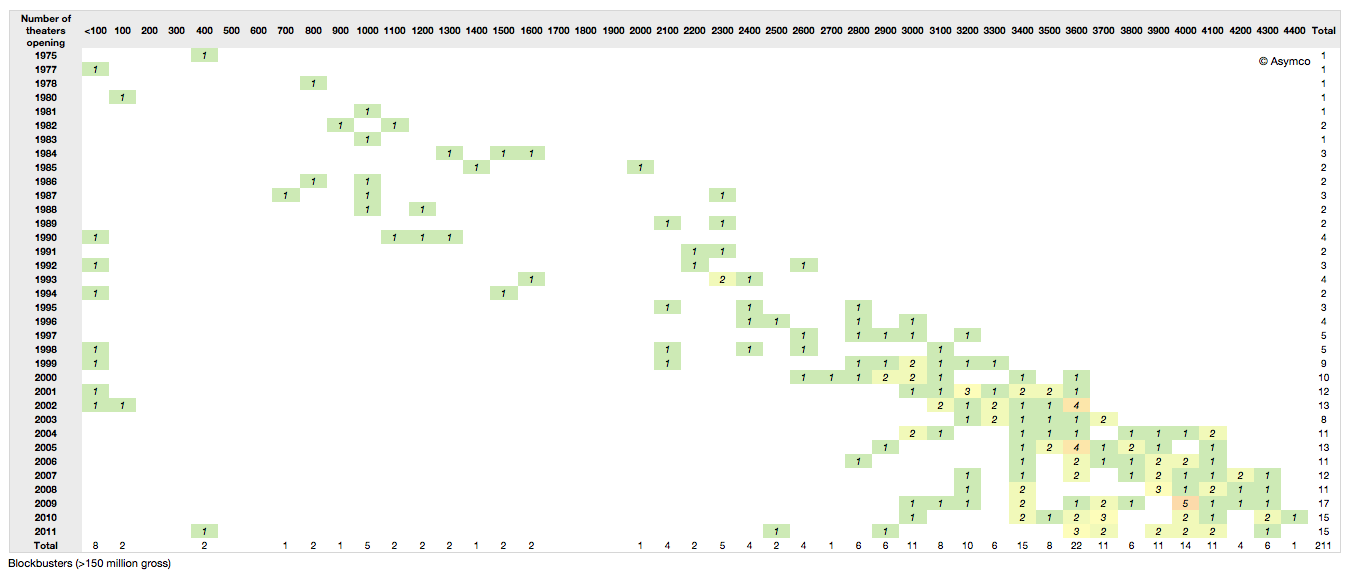

Consider the following view of release breadth (how many theaters are in an opening) by openings over time. The columns represent the number of theaters used in the opening of a movie in increments of 100. The rows are years. The cells contain the number of movies opening with that size footprint.

The pattern shows the number of theaters used in openings increasing steadily. the mean number of releases is shifting to the right. Part of the reason is that theaters shrank in size over time, but there is also the factor of needing to create a large audience at the outset of a release. The increase in “footprint” at launch (a factor of 10) is in excess of the slicing of theater sizes (a factor of two)

This broadening of launch is coincident with a decrease in viewers. As a result the notion of how movies are marketed has changed. The idea that a movie could start small and gain a following gradually through word of mouth is obsolete. That low cost approach to marketing (called “earned media exposure” in marketing) is unreliable and completely discounted.

Instead, studios manufacture an audience through paid advertising and promotion. This initial burst of viewers is essential not just for generating revenues. It’s essential to driving long-term revenues.

The reason is that technology now allows the movie to be “monetized” through multiple channels. Recorded media, broadcast rights and even in-flight entertainment are all there to milk a franchise. But there is a need to get that initial vote of confidence from one crucial audience. That happens to come only from theatrical release.

So with the scheduling pressures, the narrow window of purchased release buzz, the onus is on a broad release as quickly as possible. This holds especially true if we filter out only the blockbusters. Note how the release has increased steadily as well and that since 2000 all blockbusters released to over 3000 theaters. Compare that to Star Wars in 1977 releasing to only 30 theaters.  Notes:

Notes:

- See Jay Epstien’s The Hollywood Economist.

- Tools used include Excel, Numbers and our own App

- Data sources: Coolector, Imdb, BoxOfficeMojo, The-numbers.com

- Many thanks to David McCandless and the Information is Beautiful folks (http://www.informationisbeautiful.net) for setting up the Hollywood Budgets Award that provided us with much motivation for researching this topic.