There has been increasing chatter about a new TV being developed by Apple.

My opinion on the subject was summarized in the post called Tele Vision. I contend that a TV cannot be smart until the content it delivers becomes smart. The logical conclusion is that the value chain needs re-integration so that the component which is not good enough (the content) can be improved along the dimensions that users value. And it cannot be improved unless the direction it needs to go into is aligned with the direction of the disruptive innovator. I won’t repeat the theory here, but it suffices to say that whatever will change television will do so by re-defining the core product not just the tools we use to consume it.

But today I wanted to address another question: how do we value the opportunity? In a back-of-the-envelope manner, can we tell if this business is big enough to try to fix.

The answer depends a lot on the business model of the disruptive entrant. The entry could depend on software or advertising or hardware or distribution, and each would have a different valuation.

But for the sake of calibration, I want to start with a proxy. The basic question of how many “terminals” exist to the value networks. How many units of TVs are sold and how many could a new entrant convert to a new paradigm?

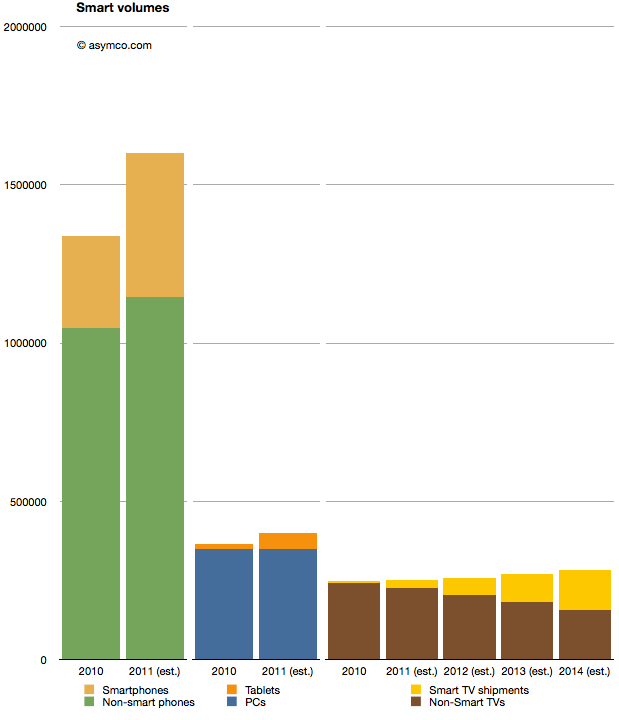

I prepared the following chart showing the world-wide TV market with a highlighted subset of so-called “smart TVs” (source TRi). The market is shown from 2010 actuals through 2014 estimates. To make it more interesting I also added similar data for two other markets. Mobile phones and PCs with their own sub-categories of smartphones and tablets as equivalent “high growth” opportunities.

When considering the opportunity, the Smart TV volumes are small relative to either tablets or smartphones. Continue reading “Assessing the Smart TV Opportunity”