To the analyst, the car industry is a wonderful study. Unlike some other “high technologies,” whose market births and deaths are separated by a few changes of the seasons the automobile industry has been around for well over a century. It has been sustained through dozens, perhaps hundreds of innovations. Almost everything about the car of a century ago has been improved.

Not only improvements to the product itself but improvements to the infrastructure that supports it: roads, gas stations, services, insurance, regulation. At the same time, its numbers have increased steadily as the car has spread to all corners of the world through waves of increased production and distribution. Although invented in Europe, the production system that allowed it to reach the mass market took hold in the US. That production system was then exported to Europe then to Japan and then to Korea and now to China.

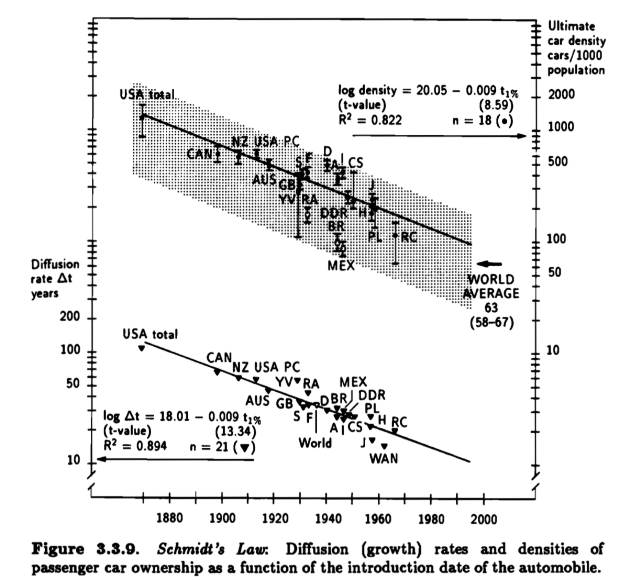

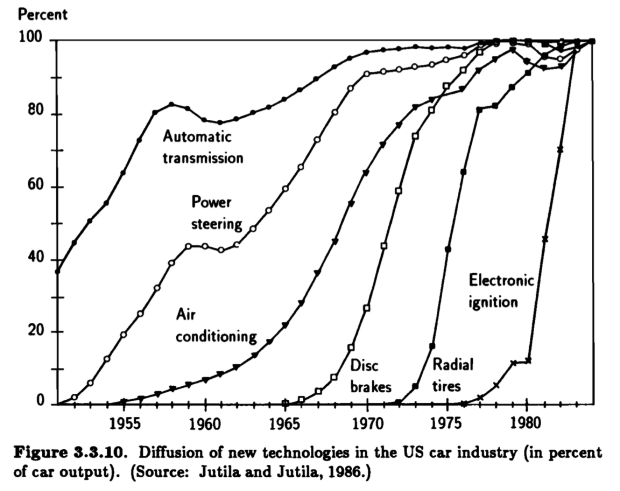

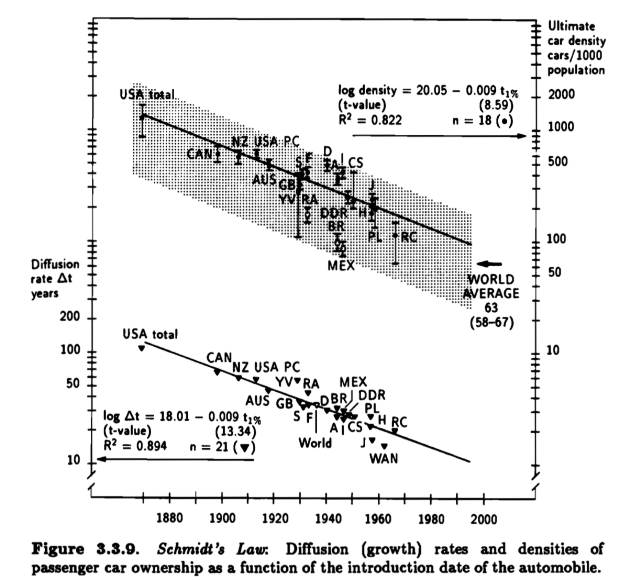

Figures 3.3.9 and 3.3.10 from Arnulf Grubler’s The Rise and Fall of Infrastructures

However, throughout this century of improvement, the business structure—the way money is made—has not changed. Even with the arrival of Volkswagen in the 1960s and Japanese automakers in the 80s, the network of incumbents has not been displaced. Newcomers have taken share, but there have been few exits suggesting that classical disruption has not taken place.

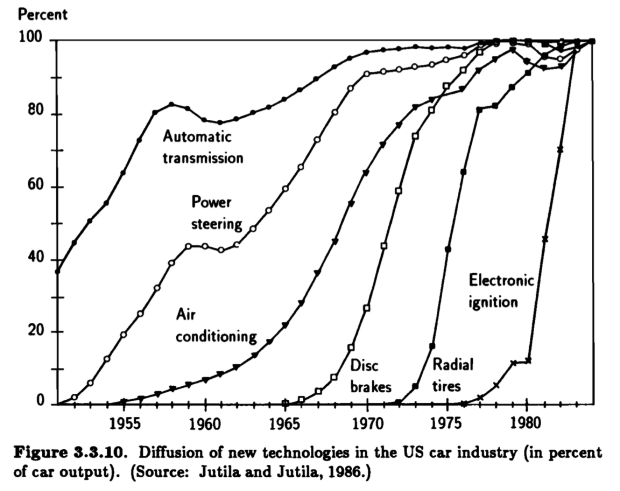

When we look at the reasons for the share displacement that did take place, we see innovation in production systems and distribution as the core causes. We see new manufacturing processes and competition against non-consumption. What we don’t see is new technologies. We don’t see diesel engines or anti-lock braking or crumple zones or fuel injection or radial tires or airbags or automatic transmission or air conditioning or electronic ignition or safety glass, or any of the other hundreds of technologies that have been adopted as causing any change in market share.

Every innovation tends to diffuse rapidly throughout the industry, being widely adopted by all manufacturers. Production systems such as the ones from Ford and Toyota have been much slower to be adopted which has offered those innovators an advantage for a few decades, but they too have eventually been widely copied and created normative behavior. The opening of new markets like Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America, Africa and China have created opportunities for local manufacturers but eventually those advantages too have or will be diminished with time.

So, given this, we have to ask if the the availability of new power storage technologies would allow an early mover to displace and move aside these established makers. To answer in the positive would imply that the challenger has an asymmetric business model—one which causes the incumbents to flee in the opposite direction. But Tesla is manufacturing cars using the same JIT processes and ramping quite slowly. Toyota-style process-driven innovation does not seem to be even in the works. There is no shortage of manufacturing capacity, indeed there is too much.

Furthermore, Tesla is selling cars in established markets competing against existing consumption. Volkswagen Beetle or Model T style competition against non-consumption does not appear to be on offer.

Tesla’s product introduction rate is relatively sedate, so a higher rate of product development which might let them “turn inside” the incumbents, does not seem likely.

Finally Tesla is introducing products priced well above average appealing to the wealthiest of customers, again causing us to ask how this might cause a luxury company to look at their solution and exclaim “Not for us!”.

Looking from every angle I am unable to find the way that Tesla is asymmetric. Disruption theory suggests that whatever causes it to survive or prosper will be embraced and extended by competitors precisely because it will also cause those competitors to survive and prosper.

The auto industry may be a lot slower than the computer industry to respond. But once the industry embraces battery-based power, it will convert a world-wide production and distribution system to sustain itself.

That does not mean Tesla is a bad business. They may carry on with Porsche-like or even BMW volumes for a long time. But that’s not a disruptive outcome, it’s a niche strategy.

There is one more point. As Tesla has chosen to share its intellectual property and as Elon Musk has stated publicly, they welcome others to build the same cars they do. So by their own admission the company does not seek to disrupt. Disruption is a competitive stance.

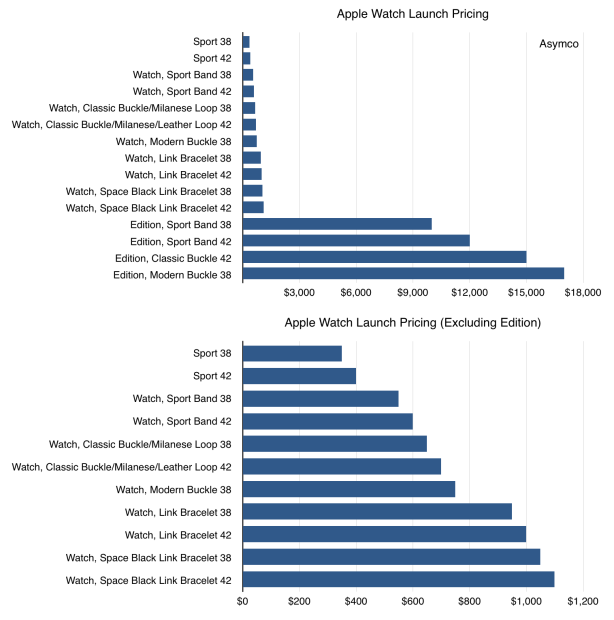

In contrast, the watches are differentiated by size, materials and bands. There are also a total of 38 watch configurations available at launch (SKUs) and another 38 bands that can be purchased separately.

In contrast, the watches are differentiated by size, materials and bands. There are also a total of 38 watch configurations available at launch (SKUs) and another 38 bands that can be purchased separately.