According to Folkore, in 1981 Apple took out a two page ad in Scientific American which explained that whereas humans cannot run as fast as other animals, a human on a bicycle is the fastest species on earth.

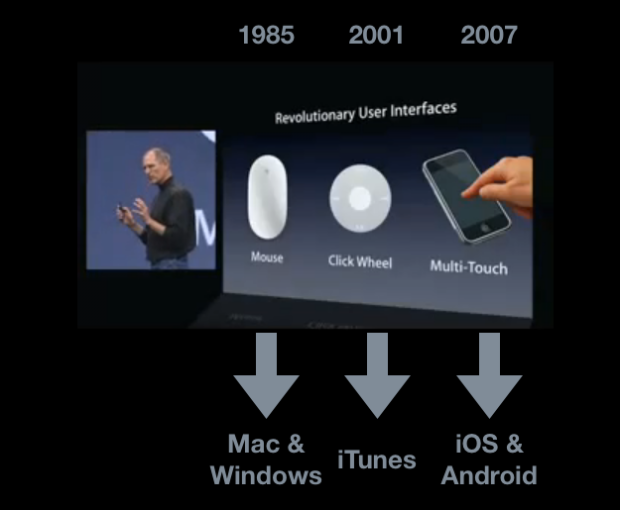

Jobs had made the observation that a computer was “a bicycle for the mind” earlier, in 1980, at a time when the decision to purchase a computer was driven by an intellectual curiosity and justified as an improvement or assistant to the intellect. It was to make the lighten the labors of our intellect.

Apple brand at the time as an appeal to the intellect via a humanistic argument. A more emotive positioning of a tool, but a tool nonetheless. This positioning evolved throughout the 80s and 90s into an “intersection of technology and the liberal arts.”

We can see how the conversation with the potential buyer was along the lines of appealing to the intellect while offering a humanist sweetener. Humanizing the product allowed it to be accepted into a world that feared the complexity and awkwardness of such a machine.

During the 2000s, with the ascent of iPod, the conversation shifted to prioritizing the emotions more than the intellect. The products had to appeal to those who wished to express and enjoy products of emotional value. Products like music and videos and the output of the arts rather than the sciences. The brand became emotional rather than intellectual. It created an aesthetic, and become culturally iconic.

During the 2010s, with the ascent of iPhone and the emergence of the Watch, the brand speaks a language of instinct, leaving intellect and emotion as secondary or tertiary voices. Instinct is visceral, lust-inducing. It seems to short-circuit any of the rational. Non-rationalism does not mean irrational. It just skips right over the head and heart and hits the gut.

One could argue that during these three decades, the organs the brand was engaging in conversation shifted from the mind to the heart and then to the glands. Those glands which release hormones and are directed by non-rational neurons. The evidence of the conversation would be in resulting products causing pupils to dilate, breaths to be quickly drawn and skin temperatures to rise.

The brand therefore has managed to move from a rational, to a neurological, to an endocrine response.

The curious thing is that during these shifts, Apple’s entry into new biological spheres of influence has been largely unchallenged. I suspect this is because emotional or instinctive products are appealing due to their lack of rationalized value. In other words, what makes a product hormonally appealing is a lack of intellectual appeal1. Apple can enter into the world of lustful appeal while lustful brands can’t enter into functional appeal.

This is a classic asymmetry which perhaps no other brand can pull off.2