The Post PC era just turned more so.

You can still get the t-shirt.

In their monthly survey update on US phone usage, comScore reported that by the end of April 74.6 million people in the U.S. owned smartphones. In the same period a year ago only 48.1 million did. The percent of smartphone users out of total phone users has reached 32%.

The following data points can also be deduced:

The following chart shows the evolution of installed base share of platforms among users of smartphones in the US. Continue reading “Peak RIM”

One of the details of Nokia’s warning which did not get a lot of attention was the mention that profitability for the current quarter could not be guaranteed. That is to say that Nokia may make a loss, perhaps for the first time in more than a decade.

This may not be that newsworthy except for the strange fact that as far as I’ve been able to observe, any company in the mobile phone market that ended up losing money has never recovered its standing in terms of share or profit (i.e. AMP index value has never recovered).

Here is a list companies that have “hit the rocks” in terms of mobile phone profitability and their fates (in no particular order). Continue reading “Does the phone market forgive failure?”

Yesterday Nokia warned that its guidance for the quarter and the year were “no longer valid.” The surprise to me is that management was surprised. In February I warned that even if Nokia could fool consumers into buying products whose platform was publicly executed, distributors and operators would not likely go along with the deception. Pricing collapse is the proof of a channel breakdown.

That seemed predictable. What I struggled with was how Nokia itself could present such an optimistic forecast. Absent any explanation, Nokia’s forecast of robust sales for Symbian products into the near future belies a failure of understanding of the dynamics of platforms and especially the impact of destruction of trust and brand value that commenced in February. Distress is a slippery slope and it does not model well in a spreadsheet. It takes a leap of non-linear faith to predict the piling-on effect on the up- and the down-side.

Faith in the company’s guidance meant that the market reacted to the bad news by discounting Nokia down to a market cap of $26.7 billion. One analyst even cut his target price down to $4/share, 57% of yesterday’s close. How can this fair? What is Nokia’s phone business worth?

In celebration of one year of Asymco.com, the Asymco store is now open.

I am extremely grateful to Michael Burgstahler of Two Tribes design for leadership in creating the first t-shirt design:

Based in the home town of Mercedes Benz and Porsche, Two Tribes has been in the creativity business for 18 years with clients like Ricoh, State Bank of Baden-Württemberg, Bosch and Siemens. They even built an app “Favorelli” and opened a little shop for home decoration.

This masterpiece, along with a logo only version is available now.

“Jim and Mike brought the company to where it is … which is part of the biggest problem they’re facing,” said Charter Equity analyst Ed Snyder, who has covered RIM since its public listing in 1997, two years before the BlackBerry was launched.

“They’re stuck in the past. They know what worked and keep playing that card and it’s not working any more, and they don’t seem to have any ideas,” he said.

via BAY STREET-As RIM struggles, talk of a change at top surfaces | Reuters.

In the case of Apple, the departure of the founder is considered a grave threat to the continuing success of the company.

In the case of RIM and Microsoft, the continued tenure of the founders is considered a grave threat to the success of the company.

Clearly, the theory that founders of successful companies can assure continuing success is flawed. Coupled to that implied causality is that departure of founders is always a problem.

Both are reflections of the idea that companies are predominantly successful (or fail) because of the skill (or incompetence) of a small group of individuals.

What the idea fails to explain is why companies fail (or succeed) as a cohort. RIM’s troubles are similar to Microsoft and to Nokia’s. Did they conspire or collude to fail simultaneously? Historically, incumbents fail simultaneously, regardless of who’s in charge.

And what about the problem that a company goes from success to failure (and vice-versa) while the same management is in charge. The “smart manager” theory of company success is as pervasive as the “stupid manager” theory of company failure. The perplexing thing is that while both of these theories are applied within the lifetime of a company, the management does not change.

Microsoft gets $5 for every HTC phone running Android, according to Citi analyst Walter Pritchard, who released a big report on Microsoft this morning.

Microsoft is getting that money thanks to a patent settlement with HTC over intellectual property infringement.

Microsoft is suing other Android phone makers, and it’s looking for $7.50 to $12.50 per device, says Pritchard.

HTC Pays Microsoft $5 Per Android Phone, Says Citi.

A rough estimate of the number of HTC Android devices shipped is 30 million. If HTC paid $5 per unit to Microsoft, that adds up to $150 million Android revenues for Microsoft.

Microsoft has admitted selling 2 million Windows Phone licenses (though not devices.) Estimating that the license fee is $15/WP phone, that makes Windows Phone revenues to date $30 million.

So Microsoft has received five times more income from Android than from Windows Phone.

Looking forward and assuming that Microsoft can receive this type of settlement from about half of the Android license takers, then the prospects of a windfall from Android dwarf the expected income from Windows Phone.

Google’s Android seems the best thing that could have happened to Microsoft’s mobile efforts, ever.

I could also calculate how the Android license income could be further funneled to Nokia (via their current agreement with Microsoft) for promotion of its phones. Thus, an Android licensee could reduce his margins in order to promote a competitor’s products.

Measurements of “share” are abundant. There is journalistic value in summarizing performance in a single figure of “share” but it usually is a very limiting view. For example in the global mobile phone market there are at least the following measurements available:

One could go on. So performance in a market can only be measured if you know to what end is that measure applied. Are you trying to determine current performance or are you assuming that the future will be different and trying to figure out what that future will look like?

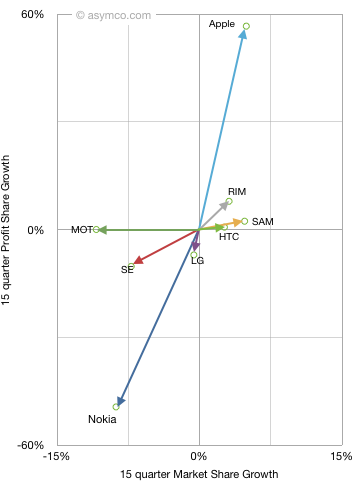

Last fall I introduced the “vector space” model of visualizing vendor performance. It shows performance along two dimensions: market share growth vs. profit share growth for a set of competitors.

When introduced, I chose a long time frame (15 quarters) to see the long-term pattern. This quarter I add two more time frames: year-on-year and sequential. This allows a view of how market change is itself changing. The three diagrams are shown below (note difference in scales)

Continue reading “A disruption is not sufficiently described by the success of some. Others must fail.”

Continue reading “A disruption is not sufficiently described by the success of some. Others must fail.”

The phone market excluding smartphones is not growing. Over a three year period it grew at 2% compounded.

The following chart show the make-up of the market by vendor.

Since it is not expanding rapidly, share over time has a lot more meaning. Continue reading “Why the phone market is resilient to low-end disruption”