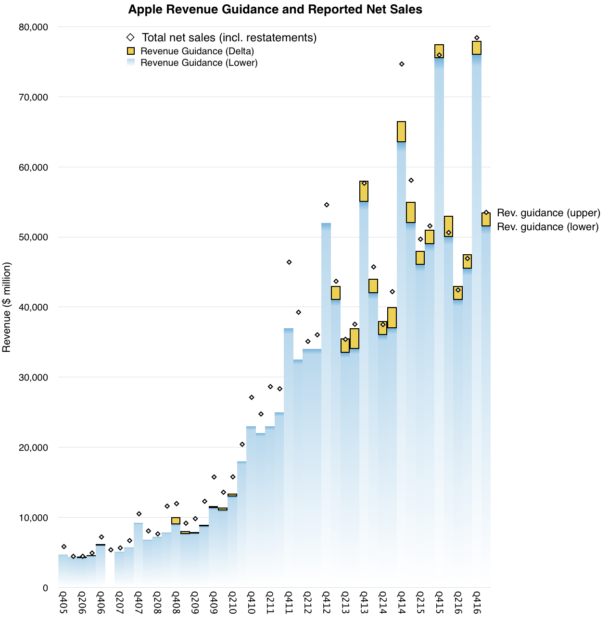

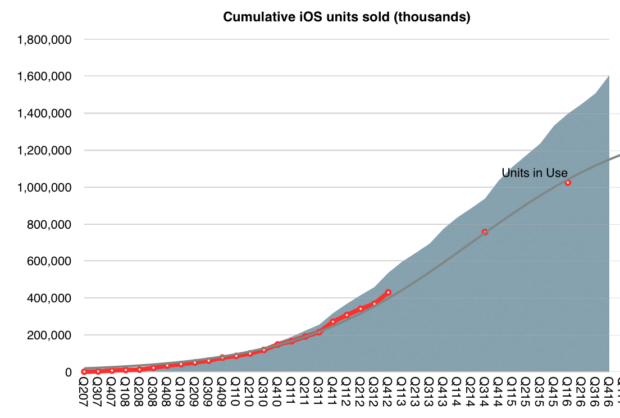

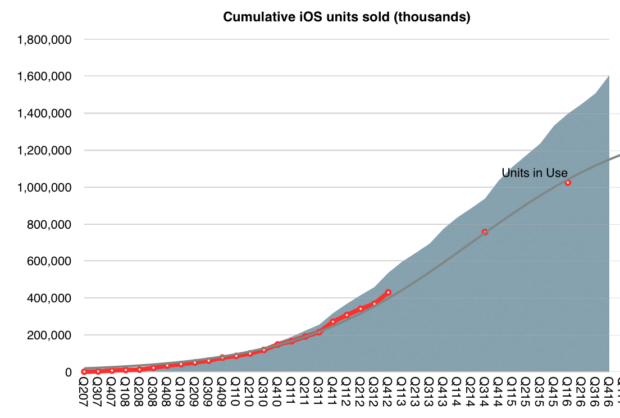

In its first 10 years, the iPhone will have sold at least 1.2 billion units, making it the most successful product of all time. The iPhone also enabled the iOS empire which includes the iPod touch, the iPad, the Apple Watch and Apple TV whose combined total unit sales will reach 1.75 billion units over 10 years. This total is likely to top 2 billion units by the end of 2018.

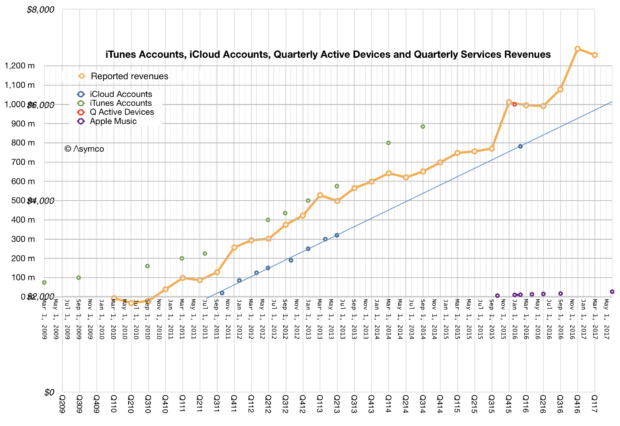

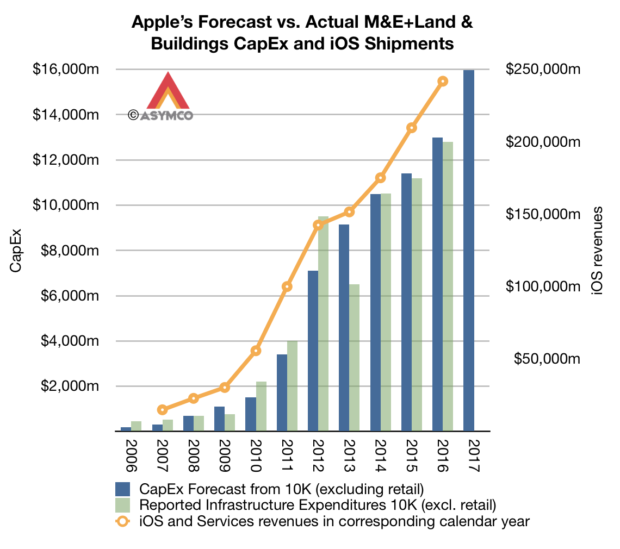

The revenues from iOS product sales will reach $980 billion by middle of this year. In addition to hardware Apple also books iOS services revenues (including content) which have totaled more than $100 billion to date.

This means that iOS will have generated over $1 trillion in revenues for Apple sometime this year.

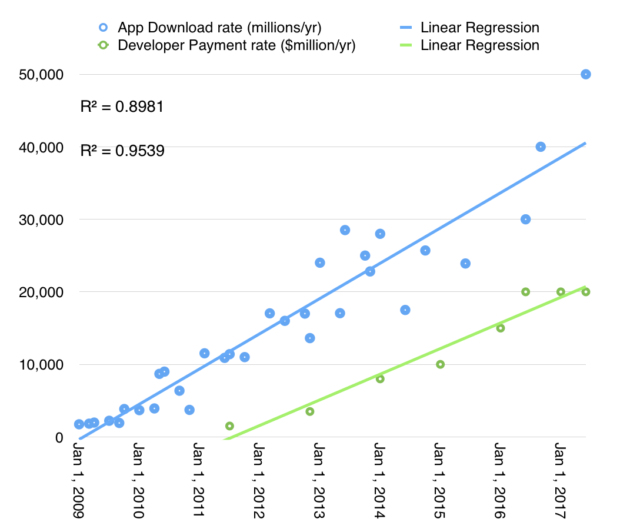

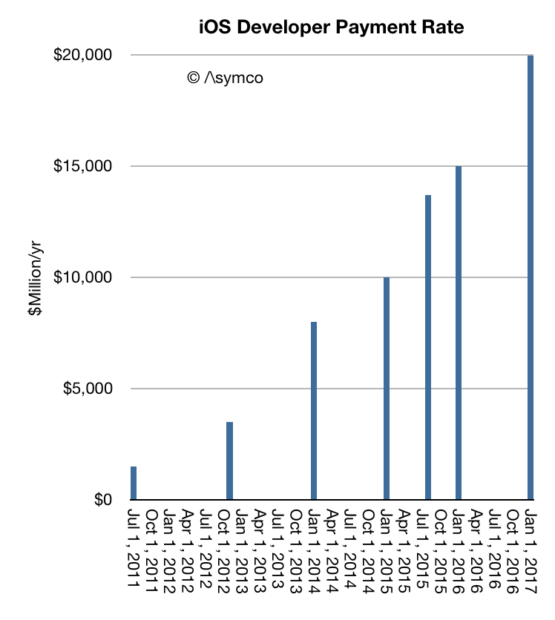

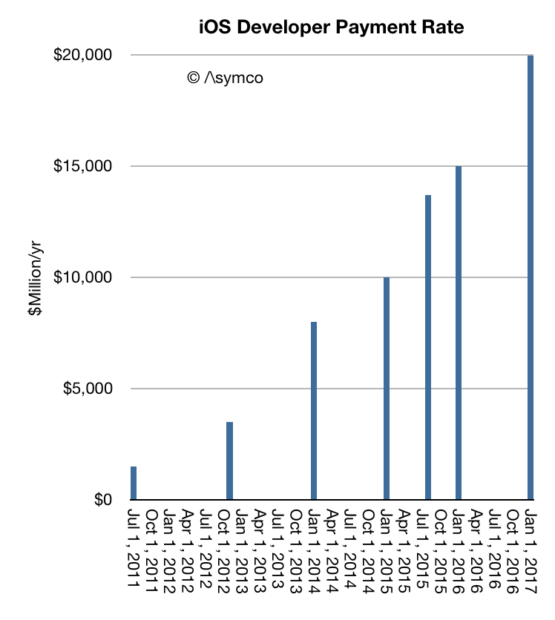

In addition, developers building apps for iOS have been paid $60 billion. The rate of payments has now reached $20 billion/yr.

Not included in this payment total are “mobile-first” or “mobile mainly” businesses such as FaceBook, Twitter, Linkedin, Tencent, YouTube, Yahoo, NetEase, Pandora Radio, Google Search, Baidu, Google Maps, Gmail, Instagram, Amazon, eBay, JD.com, Alibaba, Priceline, Expedia, Salesforce and Other Enterprise Software, Ride Sharing Apps, AirBnB and many other services which monetize independently of the App Store.

I estimate that the cumulative revenues enabled by iOS across these businesses have exceeded $500 billion, with a rate of revenue soon to reach $300 billion/yr.

The revenue numbers can only hint at the change in behavior among users. An iPhone is unlocked 80 times a day. Assuming 600 million devices in use there are 48 billion sessions on iPhones every day. 17.5 trillion sessions every year. It is these instances of interaction and engagement which are desired by all businesses built on top of the ecosystem.

These instances of engagement must be multiplied by the quality of the customers which Apple captures. iOS users spend more and are more loyal than those on alternative platform thus qualifying the platform as “premium” and thus adding to its value in the eyes of developers, content producers and service providers.

As the install base of iOS increases and as users hire the devices to do more and spend more time with them the virtuous cycle of value creation will continue and accelerate.

There is a temptation to think that such a business is fragile and will be disrupted. Challengers appear daily and the number of iPhone “killers” is not measurable. One can cite the billion users of Nokia phones which defected. One can cite the loyalty of BlackBerry users that evaporated. One can even cite the juggernaut of Windows and how it became impotent. One can cite the vast number of Android devices offered at low prices.

But there are reasons to believe that the iOS empire is far stronger and resilient.

Unlike Nokia’s phones, Apple’s product is an ecosystem with network effects and dependencies on software and services. It’s also a monolithic product with a singular interface and form factor.

Unlike BlackBerry, the iPhone does many jobs–too many to count. Indeed the iPhone evolves and changes its core value over time.

Although different in many ways from Windows there are strong similarities in terms of loyalty and persistence of users. iOS even developed a dominant position in enterprises. Microsoft’s attempt to become a hardware company is a testament to the confluence of the two business models.

And whereas Android was originally seen as the “good enough” iPhone, potentially disrupting it, it turns out to be the ersatz iPhone. Chances are higher that users will switch from Android to iPhone and not the other way. Again, the reasons have more to do with the ecosystem and quality of users (which are hard to measure) than with the hardware (which is easy to measure.)

As we look toward the second decade of the iPhone, the expectation isn’t one of another “big bang” but a process of continuous improvement. The market is nearing saturation so the goals must be to capture more switchers from Android. Apple has achieved this with the Mac: survival, persistence and eventual redemption.

More exciting is the apparent expansion of a network of ancillary “smart” accessories. The Apple Watch, the AirPods, Pencil and possible new wearables point toward a future where the iPhone is a hub to a mesh of personal devices. The seamless integration of such devices is what has always set Apple apart.