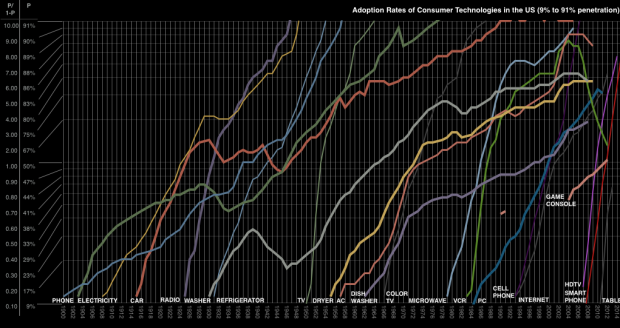

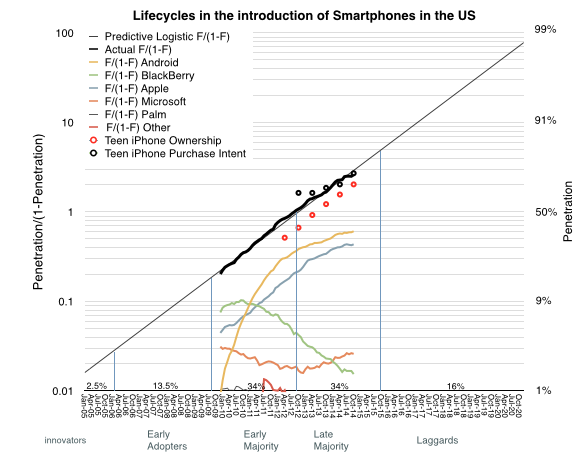

The adoption curve has been used to categorize adopters into groups by their behavior: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority and laggards. This categorization asserts that adoption is function of psychology, or the likelihood of people to act or react within social systems. [Rogers first edition 1962]

It’s a compelling model and has been proposed as a tool for firms to help with their marketing strategy. As diffusion proceeds through each adopter category, the product is re-positioned to address each group’s presumed behavior. Innovators (first 2.5% of the population) are offered novelty, a chance to experiment and uniqueness of experience; early adopters are offered a chance to create or enhance their position of social leadership; the early majority build imitate the leadership of the early adopters and justify it with productivity gains; the late majority are skeptics but, given a set of specific benefits, join the earlier adopters. Finally the laggards reluctantly agree to adopt as their preferred alternative of not adopting disappears.

The theory suggests that a firm can be successful if they modify their marketing and perhaps product mix to accommodate these adopter categories in a timely manner.

If this is the case however, why is it that those who have access to these data (i.e. who is buying and when) not to do the right thing? Why is it that during a technology adoption curve, there is a high degree of turnover in the firms which capture profits from the products that deliver this technology?

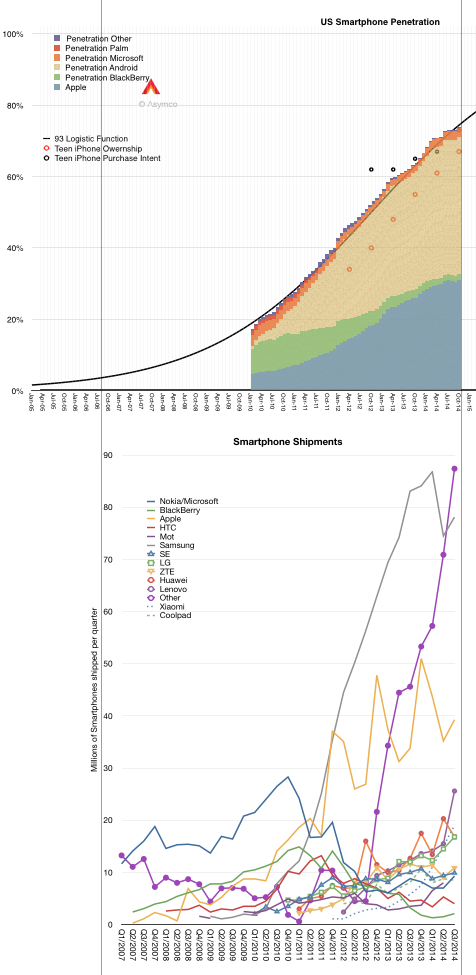

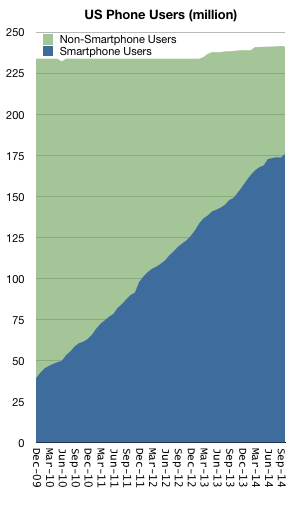

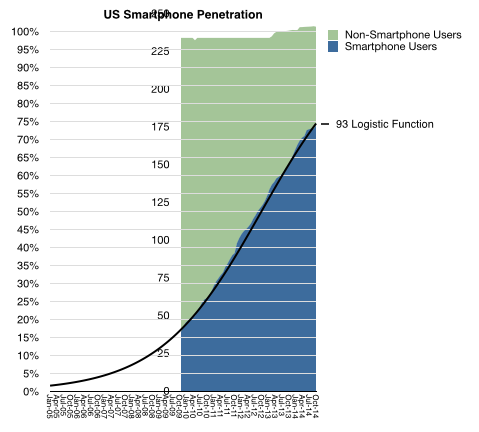

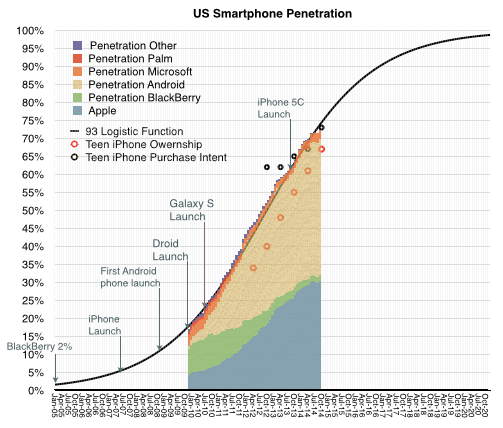

If you don’t believe this to be the case, consider the smartphone market. The data about buyers is easily obtained (even without paying a fee). Shown below is the US smartphone penetration data as obtained by comScore (including teenage survey data from Piper Jaffray).

Following the penetration data there is a second graph showing the smartphone shipments for the largest vendors as well as the sum of the “others” which make up the difference with the total market. I used vertical registration lines to align the different data sets to the same time scale.