When Clay Christensen discusses innovation (for example his talk at BoxWorks here) he puts forward theories on the causes of success and failure of innovation. Through a repertoire of case studies evoking David vs. Goliath he offers a convincing alternative to the management orthodoxy which prevents innovation, especially the meaningful disruptive kind, in established organizations. More importantly he asserts that innovation is not something that happens randomly or only through the incantations of a Chief Magical Officer. There is a process and even perhaps a repeatable process for successful innovation.

But one assumption that underlies this narrative is that innovation is good. Or more precisely, that innovation is rewarded�–making its goodness desirable through market mechanisms. The happy ending to the story is that the innovator solves the dilemma, delivers the great innovation, perhaps more than once, and then basks in glory.

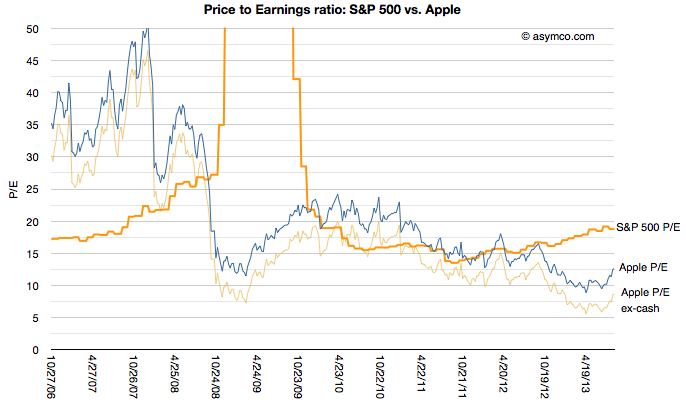

But my observation is that the way markets behave often contradicts this measure of worth of innovation.

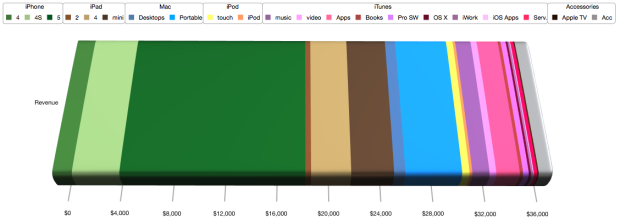

Here’s the problem: If a company produces a string of successes, the conventional wisdom is that the chances of another success are precisely zero. A company is valued based on its cash flows and foreseeable improvements to them. What it’s not valued on is its innovation flows (and foreseeable improvements to them).

In other words, if you’ve succeeded in the past, the only certainty is that you will not be able to succeed again. This assumption exists even if you’ve succeeded more than once. The wisest will offer as many excuses for being lucky more than once as they will for being lucky once. In fact, just as the illusion of a run of heads means the next coin flip must surely be a tail, a string of random successes is deemed to increase the probability that the next attempt will end in failure.

This discounting of repeatable success means that the reward for a process of innovation is zero and therefore that innovation itself is a priori value-free.[1]

This means that an innovator not only has to struggle with getting an organization to create something new (the gist of The Innovator’s Solution) but also to do so without the benefit of capital markets. When trying to raise financing for a sustainable innovation engine, the markets speak unanimously: you haven’t got a chance.

Therefore the only way an innovator can finance the next innovation is to use proceeds from a previous innovation, having faith in his engine of creation. Listening to the market would only convince the innovator that the new thing is pointless. In fact, the best idea is to stop trying.[2]

I call this The Innovator’s Curse: that building repeatable innovations provides the innovator no respite. There shall be no basking in glory, only expectations of imminent failure and attribution of success to good fortune.

When I first realized this I thought I chanced upon a remarkable paradox. That this must be some new insight into human nature. That realizing this will change everything.

But just like Disruption Theory is beautifully illustrated through the ageless David vs. Goliath parable, The Innovator’s Curse is but a retelling of this fable:

A cottager and his wife had a Goose that laid a golden egg every day. They supposed that the Goose must contain a great lump of gold in its inside, and in order to get the gold they killed it. Having done so, they found to their surprise that the Goose differed in no respect from their other geese.

Even if the cottagers were naive enough to have faith in the replicating miracle of golden egg laying geese, wise men would quickly advise them to kill it and get the gold more quickly. The Goose is doomed no matter what.

—

- A company will be priced according to products it created in the past, and that price might be significant, but as competitive pressures increase, the value itself is discounted. What is certain to be worthless however is the ability of any company to come up with something new.

- When managers give in to the temptation to stop trying they build great sustaining companies which are subject to disruption and invariably fail.