In August 2007, during the HD format wars between HD-DVD and Blu-ray format, Toshiba offered Paramount and Dreamworks $150 million to produce HD versions of their movies exclusively as HD-DVD.[1]

This type of deal is equivalent to an “advance” offered to a book author. The DVD manufacturer pays studios up-front cash for the right to make its DVDs. From an accounting point of view this is treated as an advance that the manufacturer recovers by selling the DVDs back to the studio’s video division in the same way a publisher earns back the advance it gives an author.

In this case, the payment was so large and the sales of HD-DVDs so small that Toshiba was unlikely to earn back the entire advance. The way the deal made any sense for Toshiba was that it was exclusive: the studios could not continue to release their movies in Blu-ray. The deal was done explicitly to hobble a competitor and create “critical mass” of content for its own format.

But then in March 2008, Toshiba threw in the towel and abandoned the HD-DVD format. The way the deal worked, the studios got to keep almost all of the $150 million. They then re-released all their movies in the Blu-ray format. The only “cost” to the $150 million windfall was that there was a nine month delay in the eventual release to Blu-ray–a small price to pay for an emergent format without a large install base.[2]

Platform owners go to great lengths to ensure “content” for their platform. They will, essentially, finance an ecosystem when there are barriers to entry or when competing ecosystems are far more lucrative.

This scenario for movies is being played again with Netflix, Hulu and other distributors who need to fill their pipelines. Netflix’s content acquisition costs are exploding and putting the whole company’s future in doubt.

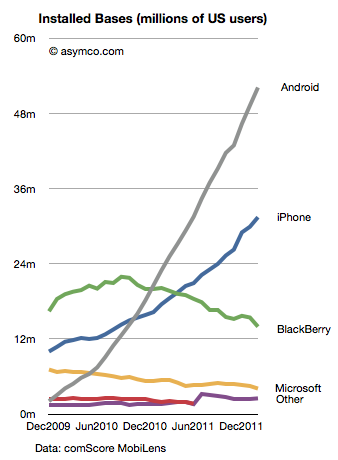

But this scenario is also being played out with app developers. Most recently, news broke that developers are receiving payments from Microsoft for Windows Phone ports of popular apps. In mobile platforms, apps are the new content and developers are the new studios. It’s also a practice that is not without precedent[3].

This is as it should be. The value of the platform lies mainly in what is built on top of it just like a foundation is not much use without a house on it. However, the practice of “priming the pump” with cash payments for porting is not ideal. Like spiffs, those who receive payments may become used to it and withhold development if there is no payment. Also, those who did not get payment offers may feel shunned and retaliate in kind. Those who receive payment may become cynical about it and may not put in the extra effort (or, more probably, outsource) to make the work spectacular.

Or, like Paramount, they may just take the money and run if/when the platform fails.

—

Notes:

- Source: The Hollywood Economist 2.0: The Hidden Financial Reality Behind the Movies by Edward Jay Epstein.

- Paramount made $250 million more from three “replication output” deals: $50 million from Toshiba for agreeing to release Titanic on DVD in time for Christmas sales, $150 million from Panasonic for agreeing to allow them to take over video replication from Thompson, and $50 million from the law firm Ziffrin, Brittenham and Circuit City stores for agreeing to support the DIVX format. Paramount got to keep the money even though DIVX never launched.

- Although it’s never been reported that Apple pays developers for building iOS apps, some developers do benefit from promotional placement and visibility during launch events and from early access to devices or SDKs under development.