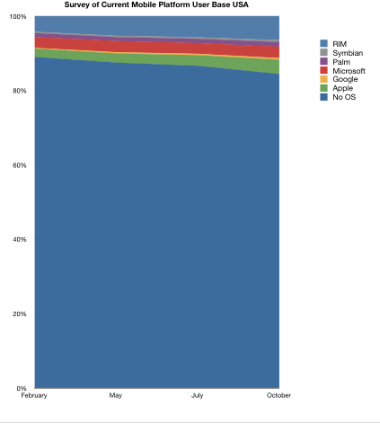

Recent data from admob shows that Android OS share is highly dependent on a single vendor (HTC). (http://metrics.admob.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/AdMob-Mobile-Metrics-Oct-09.pdf page 7)

Recent data from admob shows that Android OS share is highly dependent on a single vendor (HTC). (http://metrics.admob.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/AdMob-Mobile-Metrics-Oct-09.pdf page 7)

There is an implied message in Android advocacy that once more licensees join in, volumes will be distributed among a broad set of companies benefiting from a healthy rivalry. This broad licensing will be a boon for volumes and for user choice and the platform itself will prosper.

I’m going to argue here that there will be no healthy distribution of volumes or profits in the Android platform.

History shows that volumes for an openly licensed mobile platform concentrate in the hands of a single vendor. To illustrate, I attached a list of all the devices which shipped (to date) with a flavor of Windows Mobile. The list includes 911 different phone models (search on your own on pdadb.net under the pdamaster tab–search criteria are on the last page of the PDF).

The Windows Mobile platform “took off” and had hundreds of concurrent licensees in the middle of this decade. In spite of this wide adoption, one vendor captured 80% of the volumes for all instances of the platforms: HTC. Having started with the iPaq as a PDA and followed by being the first to market with a WinMo device, HTC dominated Windows Mobile volumes even when faced with literally hundreds of competitors. These competitors included all the big names: from PC vendors like HP, Dell and Toshiba, to cellular incumbents like Motorola, Sony Ericsson, Samsung, LG and every ODM and OEM in between. The reason HTC won is mundane: they have the experience and the distribution to make an impact and they iterate rapidly and are intimate with the details of making a tough-to-integrate product work. They basically worked their way up the value chain from a contract design shop to a branded top tier vendor.

But if you exclude HTC, dividing the number of units of WinMo shipping at any given time by the number of licensed products in the market at that time, one gets about 50,000 units/licensee. Think about that: except for HTC, an average licensee could hope to ship 50k units for any phone they engineer and market. And they also need to prepay Microsoft the minimum license fee of $10/unit (approx) for a minimum order of 50k units or half a million dollars.

This is actually a paradox. Put yourself in the shoes of a business manager at one of the potential licensees. Consider the situation where there are 200 competitors in a market all shipping undifferentiated products, and one competitor has 80% share. Would you want to be the 201st? Saying yes implies hoping to split the remaining 20% 200 ways or obtaining, on average, 0.1% share? But this is not a share of all phones, it’s a share of that platform, which itself is, at best 10% of all smartphones which make up maybe 20% of all phones. So you are committing a few million dollars to pursue (.2*.1*.001=) .00002 of a market. That target is 3 orders of magnitude less than what Apple obtained in 2 years (without the margins). It never adds up unless you expect your entry to blow out of the 20% ghetto and take on the incumbents.

As it turned out there were dozens upon dozens of business managers who opted to be the 201st (or 301st). Unsurprisingly, the result was that every Windows Mobile business plan failed (except that of HTC). Every decision to join this ecosystem on the device side was a value destroying decision, repeated 900 times.

Why?

I don’t have an answer as to why so many are taken in by this. I have a hypothesis that it has to do with excess R&D capacity (e.g. idle engineers) that compels small companies to build product with no hope of market penetration, but I cannot prove it. They may also couple the low barrier to entry to the premise from the platform vendor that a no-name licensee could be the next Dell/Acer/HTC if the platform “takes off”.

Regardless of the cause, the proliferation of WinMo SKUs did nothing for the success of the platform overall. For consumer products, it does not matter what jockeying for position happens within the value chain if the end user/developer experience is painful and uncompetitive.

Android will win or lose on the user/developer experience. It will not win or lose on the proliferation of licensees.

A Google spokesperson confirmed for eWEEK that there are 16,000 Android free and paid apps, not 20,000 as others previously reported. (iTunes App store is around 120k now with over 130k apps having been “seen”).

A Google spokesperson confirmed for eWEEK that there are 16,000 Android free and paid apps, not 20,000 as others previously reported. (iTunes App store is around 120k now with over 130k apps having been “seen”).